I’ve now finalized my “Bozeman Check-in” series, which means that it is time yet again for another “Things I’ve Learned” post. This is the third of these posts, coming after my Denver and Santa Fe editions. Just like before, I’ve settled on 39 items, for no specific reason other than that 39 is a good strong odd number.

The general purpose of this post is the same as before; to recount things I’ve learned about myself, about life, and about the world. So, in the spirit of Big Blue Bear here are is a list of things which I learned and/or were affirmed to me during 10.5 weeks in The Treasure State.

Things I “Learned” in Bozeman:

aka, what I discovered while yet still peaking into the window of life, just like Big Blue Bear

- It can snow in Montana 12 months out of the year.

. - I am so totally not a city person, I can only continue to reiterate this in these posts.

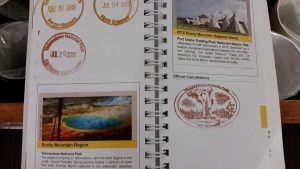

. - Yellowstone National Park is amazing, but I think if (when) I return I’d like to visit on one of the “border” seasons rather than during the peak period, or heck, maybe even in winter though I’d need to acquire a snowmobile for large areas of the park – but that would be fun in and of itself.

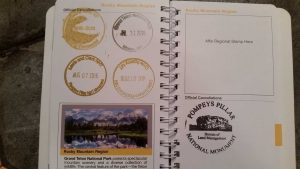

. - The Teton Range is one of the most magnificent mountain ranges I have ever seen and I’ve been fortunate to see a lot of them. It’s mostly due to their jagged peaks and steep inclines rather than their raw height as I’ve seen much higher mountains.

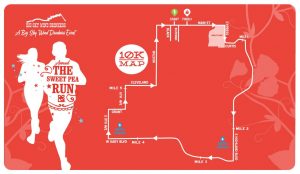

. - I can run a 10k. This is really awesome. There was a time when I didn’t think I’d be able to run anymore.

. - Having the summit of a mountain all to yourself, a T-Rex, and some mountain goats is an unbelievable experience.

. - There are places left where you can walk through a seemingly endless field of wildflowers – just like the movies.

. - I will never stop loving dinosaurs. It’s too strongly embedded in my boy-DNA.

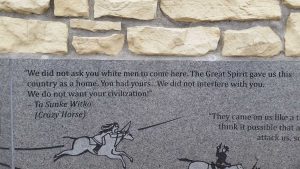

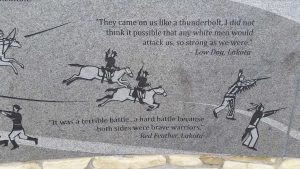

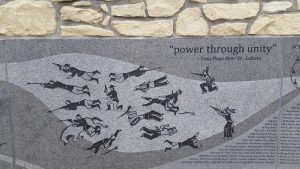

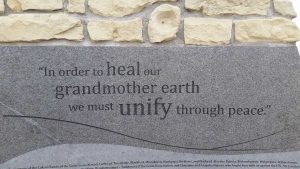

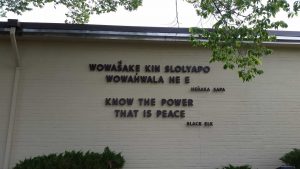

. - Just to repeat this from the Santa Fe version of this post, we really fucked over the Native Americans.

- Bison stick out their tongues and bellow at each other and it’s one of the funniest and coolest things you’ll ever see.

- Wolves are seriously bigger than you think, I mean, wow, they are huge.

- There is a Coyote who lives near Tower Junction in Yellowstone National Park who really likes to show off for cars.

- Bears are incredibly intelligent creatures who are far less likely to hurt you than you are to hurt them. Don’t believe me? Educate yourself.

- That said, Grizzly Bears are crazy huge, so be “Bear Aware.”

- The drivers in Montana are terrible. It’s not just me saying this either, Montana has frequently be ranked as one of the “Worst States” for drivers. They seem to live for the thrill of forcing you to slam on your breaks by pulling out in front of you. I think part of it has to do with the fact that most of Montana involves going on a 500 mile long straight road at 150mph. They don’t seem to know how to drive around other vehicles very well. Also, it’s state law in Montana that you aren’t allowed to drive without a truck tailgating you.

- I still feel comfortable in environmental law, but I honestly have no idea where my life path will continue to take me.

- When he wants to Tristen is capable of downing and consuming an adult deer. Don’t mess with that boy (but don’t tell him that, his head is big enough already).

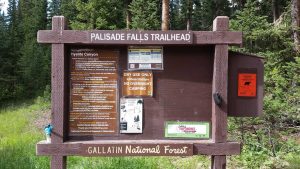

- Climbing mountains is challenging but one of the most fulfilling experiences I’ve had on this earth.

- Ravens are creepy as shit.

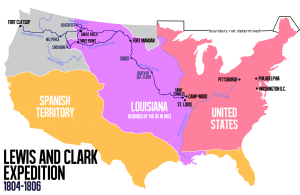

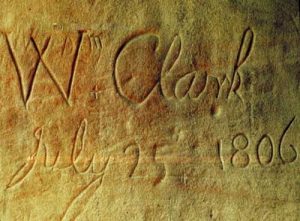

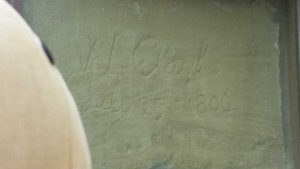

- I will drive 180 miles to see a signature carved in a rock and I won’t regret it for a second.

- You can cross the continental divide like 16 times in one day in Wyoming.

- The great plains have their own beauty to them. Seeing wind blow through the seemingly endless fields is a captivating experience that is hard to describe.

- Humidity is the work of Satan.

- Mormons don’t all wear signs saying “Hey I’m a Mormon!” – In fact I didn’t realize my landlords were Mormons until after about 8 weeks into the summer.

- There is a Moose, Wyoming and a Squirrel, Idaho – I’ve been to Moose and will hopefully make it to Squirrel one day.

- Speaking of animal names, my two favorite radio stations in the Bozeman area where “The Moose” and “The Hawk.”

- Having drove a 2016 Toyota Corolla, Ford Focus, and Mazda III – I’d say that the Toyota had the best gas mileage, the Focus handled the best, and the Mazda had the most “get-up-and-go” though I’ll never be able to afford any of them. 🙂

- Tristen loves him some “Reddy Roosevelt.”

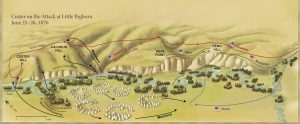

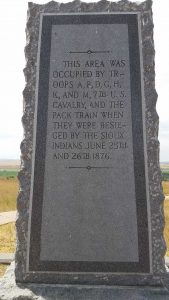

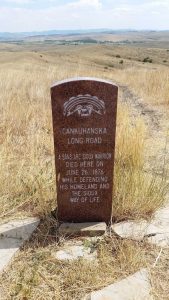

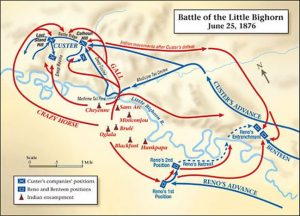

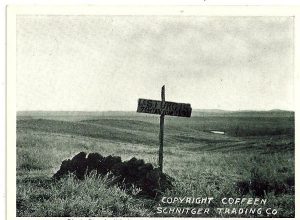

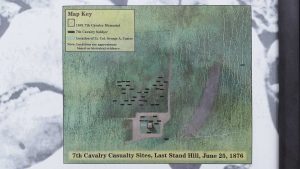

- There were 7th Cavalry survivors at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, and Custer might not be as much to singularly blame as I was taught in high school (not that my school had high academic standards by any means).

- There is a Boiling River in Yellowstone that you can swim in without dying in agony, but make no mistake, you could definitely die in agony in it if you wanted such a thing.

- A fair number of tourists are incomprehensibly stupid.

- Most people driving RVs shouldn’t be.

- Despite my constant self-doubt, I seem to always receive really good and positive feedback from all my supervisors. Sure, I’m not much of an academic these days (I’ve cared weirdly little about grades since starting law school), but when it comes time to rally in the trenches, I seem to be more capable than I give myself credit for.

- Dog people are almost as bad as kid people. Almost.

- Montana is prone to 40+ degree temperature swings in the course of one day. Brace thyself.

- Montana is also prone to hail storms the likes of which I’d never seen before.

- Speaking of which, having a metal roof is fun and games until a hail storm unleashes hail the size of ping-pong balls at 3am and sends your T-Rex into high-adrenaline carnivore frenzy mode and he screams about the “Krauts” for the next two hours while kicking holes in walls.

- Ask people questions. You’ll never know what you might learn. Some people I never thought I’d have anything in common with ended up having extremely interesting lives and had traveled the same path of the beam as I. Life continues to show me that there is seldom reason not to try to learn things, even when the act of asking can be a personal challenge.

- Lastly, and most importantly: “The Mountains are Calling and I must Go.” ~John Muir

I see what you mean.