This post is a bit outside of my usual blogging area, but I think it will be a lot of fun regardless. This is actually a modified version of an email I sent to Meem, SB, and Daryl 1 back in January. Because I wanted to memorialize it a bit better as well as share it with a larger audience, I’ve decided to “port” it over to Dinosaur Bear. While I’ve changed some parts, added some photos, and reworked the formatting (which was horribly broke and ultimately required no less than 30 formatting edits), it’s largely the same general thesis as it was before – just more blog friendly.

This is definitely one of those times where I will deeply analyze and research something that was probably never really intended to be subjected to much scrutiny, or maybe it was, and that is what makes it fun. Still, if you have no interest in an in-depth discussion of old cartoons, or seeing my more analytical side, then you probably won’t find much of interest in this post. That said, I’d still recommend you give it a chance simply because there is some very interesting stuff in here.

I’m going to be talking about the 1987 film, The Brave Little Toaster, more specifically, I’m going to focus on its song, “Worthless.”

I’m going to be talking about the 1987 film, The Brave Little Toaster, more specifically, I’m going to focus on its song, “Worthless.”

Most people who were kids (or had kids) in the 87′ – 97′ range are familiar with The Brave Little Toaster (TBLT). From its endearing characters to its not-so-subtle sexual/dependent undertones for the Master. If you don’t remember it well enough (or if you’ve never seen it), you should watch it again sometime, it’s on YouTube for free. Anyways, it’s billed as a Disney movie, but the thing is, it’s not. It was actually produced by Hyperion Animation and The Kushner-Locke Company. Worth noting: the film’s entire budget was 2.3 million dollars. Which might seem like a lot for 1987 and an animation, but it was in fact dismal. For comparison the average Disney animation in that same year received 24 million dollars. TBLT was directed by Jerry Rees. It was based on the novel The Brave Little Toaster: A Bedtime Story For Small Appliances, by Thomas Disch, which was written in 1980. Since the film’s budget was so low all the production was done in Taiwan. In fact, the American crew spent half a year over there overseeing production. That is why the animation isn’t quite as sharp as other cartoons from the late 80s – they used lower skilled artists who were MUCH cheaper. That being said, production values were still very high for what they had to work with. The production crew was also quite well trained, in fact two members – John Lasseter and Joe Ranft would later go on to raise Pixar to the powerhouse it is today and were largely responsible for writing Toy Story – think of the similarities between TBLT and the Toy Story franchise: makes sense!

Disney only acquired the rights to the movie after the Sundance film festival where it premiered.* Disney then proceeded to ruin most of the success TBLT could have had by making it direct to TV for a Disney Pay-Per-View channel that failed extremely quickly.

*[Side Note 1: TBLT actually won with the judges at Sundance, but administration made them give the best film to another entry, because they didn’t want a cartoon to win and “discredit” the festival]

Anyways, my point in all this is to say that TBLT was largely uninhibited by bureaucracy. They could do things as an independent studio that someone like Disney would never allow them to do. The most obvious example is the evil clown scene (which, to date, is still censored on every Disney-owned rerun of the movie).

But there were also more subtle things, such as one of the appliances during the song “It’s a B-Movie” having boobs. No seriously, it does not take much imagination to see the boobs, just skip to 0:40 in that video I linked. But unlike many other such “hidden” sexual innuendos in kids movies, TBLT didn’t stop there, it went further to show murder on screen.

Granted, it was a blender, but given that these are anthropomorphic creatures, when it gets ripped asunder and then you see oil leaking off the table, that’s pretty much a murder (never mind all the cars from the junk yard, but we’ll get to that soon enough).

Essentially our team of appliances are seeking the adult Master. They’ve actually managed to find his apartment in the city after being abandoned in his childhood cabin, but the new appliances throw them in the trash. They then arrive at this dump where they are in the midst of facing a real peril: the magnet.

The giant magnet, much like the other anthropomorphic characters is driven by the prime directive of completing his task, as all good machines do. That means he will crush anyone or anything in the junkyard, end of story. Soon enough, our appliance team realizes that they aren’t alone: the sea of dilapidated automobiles about to meet a horrific fate have a story to tell.

0

Now, without reading anything else in this post after this paragraph, go watch. If you didn’t click any of the other scenes above, that’s no big deal, but you really have to watch the “Worthless” song as it is in the film to have any idea what I am talking about. I linked the “No Interruptions” version since the original is busted up between cuts to other scenes, which don’t matter for the purpose of this post. So ignore the little clips in-between. The quality is fairly poor, the longer version has better quality but it adds over 2 minutes of completely irrelevant (for our purposes) material. Also, the low quality means the lips are a bit out of sync, but since this is a cartoon it really isn’t that troublesome. If it does really bother you though, you can easily find the higher quality long version, with the clips in between.

0

Even without reading what I am about to say, it’s fairly easy to see that this is a bit of a darker song for a children’s cartoon. First, the cars are crushed into tiny cubes, quite aware of the vicious death awaiting them as they go down the conveyor belt. The lyrics themselves are also melancholy. Not that that is especially surprising given that this is pretty much a death yard. I remember watching this as a kid, I liked the song, but even then I remember being bothered by something about this scene (The Blender scene bothered me more, to be fair – but there was just something “not right” with this scene to me, even then).

So, with that in your head. Here is some more information about the song. First, the music in TBLT was composed by David Newman, who has worked on many, many films, ranging from TBLT to The Sandlot, to Dr. Doolittle, to Never Been Kissed. The lyrics came almost entirely from Van Dyke Parks, who wrote extensively for the Beach Boys, as well as working with other artists such as Ringo Starr (“Worthless” was one of the songs written by Parks). However, like many older films, there were a slew of people who worked on TBLT without being credited. One such person was Jim Cypherd, a music producer who produced none other than Meat Loaf’s Bat Out of Hell. Yes, TBLT has a link to Bat Out of Hell. Cypherd had a connection to famous Italian film-maker Federico Fellini, namely, they had spoken about Cypherd assisting with some sound production of some of Fellini’s later works, which never panned out. That being said, Cypherd became a fan of Fellini’s films, especially 8 1/2 which is considered by many to be Fellini’s greatest work. A big theme of that movie was the dangers of rampant and rapid modernization (which is a strong sub-theme in TLBT – see “Cutting Edge“) I’ll return to this in a minute, but for now just remember that Fellini wasn’t actually involved in TBLT but that there was a professional connection there.

Alright, now you’re ready to start parsing through the song a second time. I’m going to work through the scenes and lyrics. Obviously you won’t be able to follow along in real time. But for reference I am using the “No Interruptions” version of the song I linked above (and here again, for reference).

As a point of reference, I’m not just blindly making this all up. 😛 Some of it is parsed from various interviews Rees has given over the years, plus secondary interviews such as Cypherd and Parks. There is, admittedly, also a bit of sleuthing to pair together the “most likely” interpretations, but in light of that I’ve tried to minimize raw guesses. Like most good works, there is much left up to interpretation and what follows is my personal thoughts on the matter. Below I progress through the song, you’ll find lyrics in italics (with a few exceptions where I use them for emphasis) and my thoughts in standard block letters.

The Brave Little Toaster – Worthless

I must confess one more dusty road

Would be just a road too long

0

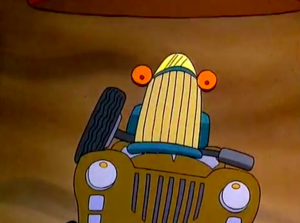

This car serves as an introduction not just to the song itself, but also to the deathly environment of the scrap yard. His lyrics are fairly straightforward, albeit grim. The first line: I Can’t take this kind of pressure, is, like most of the song, a dual-purpose lyric. Not only is he getting smashed (while being grabbed) by the magnet and about to be entirely obliterated by the crusher, he is crumbling beneath the requirements of his life. In simpler terms, he “can’t deal with it.” His second and third lines: I must confess one more dusty road, Would be just a road too long. Make it apparent that he is tired, quite possibly depressed. He just cannot move forward (literally) in life anymore. It seems like this car has given up and is ready to go. However, notice his final moments. Specifically 0:23 onwards. In the last moments of his life, he looks up in horror. His demeanor was quite calm up until that point, but then suddenly, in those last moments, it’s almost as if he wanted to live. The Blue Car represents the finality of death, he serves as a warning towards “giving up” since you might not realize what you have until it’s too late.

Worthless

And now we hear our background chant of Worthless by the cars in the junkyard. It’s easy to miss this the first time around. But they sing Worthless at the exact moment that the mangled body of the Blue Car begins to move away from the screen and down the conveyor belt. Was his death worthless, or was it his life? We aren’t given an answer for now.

Pink Convertible

I just can’t- I just can’t- I just can’t seem to get started

Don’t have the heart to live in the fast lane

All that is past and gone

Worthless

Back to the chorus. This time it seems a bit more clear that it was the death that was worthless, but maybe that is being optimistic. A clear hint is the dialogue, “And there ain’t nothin’ you can do about it!” quickly followed by “Pardon me while I panic!” This seems to allude to worthlessness being something that is applied to us by others. We’ll revisit this in a moment.

I come from KC, Missouri

And I got my kicks out on Route 66

Every truck stop from Butte to MO

Motown to Old Alabama

From Texarkana and east of Savannah

From Tampa to old Kokomo

I’d also point out that at 1:15 his “guts” spray all over the watching cars. Dark enough for you yet?

Worthless

Here Worthless likely ties more into the events that brought about the end of Hot-Rod. Had Americana not died out, he would likely have still be running the open road. Are the cars worthless, or is it their masters?

I must confess I’m impressed how I did

And I wonder how close that I came

Now I get a sinking sensation

I was the top of the line

Out of sight, out of mind

So much for fortune and fame

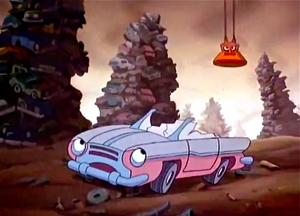

0

Another reference to Indiana. I’m not sure if that is just topical or if there is more to it, I’m going to go with topical for now. These lyrics start off a bit more positive. I once ran the Indy 500, I must confess I’m impressed how I did, And I wonder how close that I came. Seems fair enough, he is looking back to his big race, and while he didn’t win, he was impressed with himself. He has a bit of self doubt, but on the whole he seems impressed (possibly in spite of himself) that he did as well as he did. However, notice how quickly his demeanor changes at 1:30. The visuals sync exactly with the lyrics, Indy Car is literally sinking as he gets a sinking sensation. However, he is also coming to terms with something horrifying about his death. Since he didn’t win, no one will remember him. He was top of the line, but now he is out of sight and out of mind, so much for his fortune and fame. No one remembers who came in second place. We are a culture of winners, second place is the first loser. We do not value the fact that he was proud of himself, he will never be remembered. As he is crushed, so too his is very existence.

Texan Limo

Once took a Texan to a wedding

Once took a Texan to a wedding

He kept forgetting his loneliness

Letting his thoughts turn to home

And returned

These lyrics mark a turning point. While the preceding lyrics are fairly straight-forward (even if the audience of children will miss them, as per the design) the Texan Limo’s lyrics get a bit cryptic. If it wasn’t obvious from the long horns, she mentions she is from Texas, or at the very least took a Texan to a wedding. Now here I’m honestly a bit stumped. We have surprisingly little information about this song to start with. But the Texan Limo’s portion has no available backstory to it, or at least nothing that I could find. For instance, why does she repeat “Once took a Texan to a wedding” twice? In a song so full of symbolism it’s either a red herring, or it has a hidden purpose. Newman, Parks, Rees, Cypherd, etc. have been silent on the matter (or no one has asked, either or). Now opinion is mixed on the next part. He kept forgetting his loneliness, Letting his thoughts turn to home, And returned. You can go two ways with this. Was the Texan a guest, or was he the Groom? Either way potentially makes sense. I believe it was the Groom. He got cold feet. He “forgot” what it was like to be lonely, he wanted to “go back to the way things used to be” (home) and so he “returned.” However, the way “And returned” is just sort of hanging at the end of the song seems like maybe his ending wasn’t so “happy” after all. It’s a bit nihilistic, but that meshes well with the song as a whole.

This isn’t the end of the Texan Limo though, the story deepens in a moment.

I beg your pardon, it’s quite hard enough

Just living with the stuff I have learned

0

Given how quickly the scene goes by a lot of people miss that this car is actually a hearse. If you miss that it might seem like he is talking about taking someone to a funeral. Well he is, but it wasn’t a guest, it was the deceased. This car has had a corpse inside of him. It’s also probable that even though he refers to “a man” in a singular sense, he’s likely took a large number of deceased people to their final resting place. I beg your pardon, it’s quite hard enough, Just living with the stuff I have learned. These two lines are interesting. He is defiant: I beg your pardon, its quite hard enough just living with the stuff I have learned. Someone is asking him to do more, maybe it’s an internal voice, maybe it was a master. But he was done, he had had enough. As a hearse, he has probably witnessed the worst of people and the worst of times. He was in many respects a modern day Charon.

And while his lyrics are dark enough as is. Notice how the scene plays out from 1:51 onwards. It’s the exact same scene as the Texan Limo. Now, from a practical perspective this could be done as a cost-cutting measure. That argument may well ring true at least for the first part, but notice what happens next: the Hearse is dropped onto the Texan Limo (Never mind that the Texan Limo would have been crushed a long time before that given how fast she was moving, but cartoons are a perfect example of suspension of disbelief anyways). These are the only two cars in the entire song that die together. It might have been left at that had Cypherd not mentioned in an interview with a blogger that they “deliberately paired those two cars.” This likely means one of two things. First, the Groom/Guest from Fancy Car killed himself and the Hearse bore his body. Or two, the “joy” of a wedding (fragmented and hollow as it often actually is) is contrasted against “death.” A lot of people buy into the Groom suicide, I think that’s too much of a stretch and a bit gimmicky. I think they are pairing a false wedding with death.

Worthless

We return to the chorus for the first time in a bit. Here I think it’s pretty clear. We are shifting even further from the cars themselves. “Worthless” isn’t just referring to the state of the automobiles, it’s referring to the problems and socially created dogmas that were placed on their masters which trickled down to them.

Once drove a surf at the sunset

There were bikinis and buns, there were weenies*

Fellini just couldn’t forgetPico, let’s go up to Zuma

Pico, let’s go up to Zuma

From Zuma to Yuma, the rumor was

I had a hand in the lay of the land

0

And here we have a big reference to Fellini. These lyrics aren’t too grim, but they do deal with something a bit serious that you would never get as a child and most likely miss even as an adult. Remember, it was Parks who wrote these lyrics. Parks had worked very closely with Brian Wilson (of the Beach Boys). So if you read Woodie’s lyrics through that lens, nothing seems especially abnormal. The Woodie is evoking surf culture and the lyrics alone are quite similar to “Surf City,” the 1963 song which was the first “surf music” song to ever hit number one on the Billboard Charts. However, like the rest of Worthless, the lyrics go deeper than that. Mainly this portion: There were bikinis and buns, there were weenies, Fellini just couldn’t forget.* Ok, so you don’t even need to know the details to get sexual vibes from this. And you would be spot on. Federico Fellini was known as a loose, sexually frustrated man. He grew up strictly Roman Catholic and later critiqued all the restrictions and guilt-inducing tenets he felt such an upbringing entailed. As such, many of his films dealt with his latent and repressed sexuality, especially towards younger women. In fact, almost all of his films contained autobiographical elements that dealt with subtle sexual issues as Fellini grappled with them. Further, Fellini loved to break to the fourth-wall, not in any long or drawn out ways, just a quick break followed by a return to the film as expected. Cypherd convinced Newman, Parks, and Rees to include a bit of Fellini in the lyrics, especially since Fellini was so well known on the west coast (California) for being a bit of a wild one. So literally, these lyrics refer to a beach party with attractive men and women and Fellini just couldn’t forget the sexual energy. It’s about sex, it’s always about sex.

Now, as for Pico, let’s go up to Zuma. We don’t know. Zuma is a beach, that much is easy. We have no idea who or what Pico is. Interpretations go two ways. One, Pico is a person, possibly a random surf person (Woodie’s master) or Pico was a hidden boy-toy sex object of Fellini (who was likely bisexual, but this was never actually confirmed). Cypherd, et. al. were mum about this part of the song. Two, it’s referring to Pico Boulevard, which is logical, but Pico doesn’t go anywhere near Zuma beach. So take your pick on this one. It’s also repeated twice, with no real reason given, perhaps it’s just an auditory device (same for the Texan Limo’s verses). I had a hand in the lay of the land is also divided in interpretation. One theory is that the Woodie herself is talking about changing the lay of the land, surf culture, the western movement of the population, big Hollywood, movie stars, etc. It’s all quite possible and it’s probably the take I go with. The second theory is that this is also about Fellini and it is him talking about the very large impact he had on cinematographic history and Hollywood itself. So basically either a “culture” or an “individual.”

Speaking of Fellini, if it wasn’t obvious by now. Watch at 2:16. What happens?

The Woodie loses one of her eyes, which literally breaks the fourth wall (er, glass): as Lampy looks outward at the audience and is shocked by what he sees. The Woodie then lands on her back, unable to escape. She is either rocking in an attempt to escape or is simply rocking because of momentum. It’s a bit hard to tell how she feels about dying given the style and prose of her lyrics.

I worked on a reservation

(Ooh…ooh…)

On a bus back to old Santa Fe?Once in an Indian Nation,

I took the kids on the skids where the Hopi was happy

’til I heard ’em say…

“You’re worthless.”

This is a scathing indictment of our treatment of the Native Americans in addition to ourselves. See what happened? He was happy with himself, but then someone said “You’re Worthless” (pretty much paralleling colonialism) and cast him aside. What right did they have to call him worthless? What right do we have to call others worthless? Is their subsequent reaction to it blaming the victim, or should we never have labeled them as such in the first place?

But it gets even darker. Watch carefully. Pickup Truck kills himself. He runs away from the magnet successfully. And if you look at the angle it’s quite likely that he drives straight onto the conveyor belt himself and then just sits there until he dies (and sprays all over our star appliances). Yes, TBLT just depicted a suicide. He had found purpose, which was then stripped from him due to him being labeled worthless. Society no longer needed him, so he killed himself rather than being carried away by the magnet. It was a last act of defiance. It serves to show that there was nothing wrong with him, but rather we created the flaw in him.

========

And that ends the song, followed in the film by Master about getting killed by the Magnet and Crusher only to be saved by the Toaster who flings herself* into the gears and is mutilated in ungodly ways without cutting away right before the children’s eyes (again, it’s all on YouTube). Of course Master fixes the toaster, but still, it’s intense for a kid’s movie.

*[Side note 3: When I originally wrote this post I was under the presumption that Toaster was canonically a girl. This stemmed from a series of comments made by Rees in which he referred to Toaster as a girl (the most recent example was an AMA he did on Reddit). My perspective was bolstered by Deanna Oliver (Toaster’s voice actress) who had originally referred to the Toaster as a girl as well. As for the original novel version, Disch had only referred to Toaster as an “it.” Thus, with Dees and Oliver referring to the Toaster as female and the original source material not giving the toaster a sex, I figured I’d follow the presumptions of the director and voice actress. However, upon closer inspection there is a moment in the film where the Toaster is referenced as “guy” (the scene with the air conditioner). To add to that, in a more modern (though now several years old itself) interview that featured both Rees and Oliver, Oliver refers to the Toaster as a “boy” and Rees doesn’t say anything about it. Now, in the context of Oliver’s quote “I can’t be the Toaster, the Toaster is a boy!” – it isn’t entirely clear that the Toaster was, in fact, a boy or that Oliver had misinterpreted the Toaster’s sex (which is easy to do, thus the 30+ years of debate on the topic) early in the audition process. As for Rees, perhaps he didn’t want to interject over Oliver, didn’t care, didn’t catch it, or – also possible – he agreed with it. So, in the end, you can argue it either way.

The most recent comment on Toaster’s sex is from Rees and he refers to toaster as female. However, the film itself has one character to refer to Toaster as a “guy” (which also arguably isn’t definitively male, but that’s stretching it) and the voice actress has variably referred to Toaster as both male and female. As such, you can make decent arguments either way as to Toaster’s sex. The most logical argument probably boils down to the in-film (and thus arguably most definitive) use of the word “guy” against Rees’s repeated and fairly recent references to Toaster as female. But the debate shall rage on and at the end of the day whether Toaster is a he, a she, or an “it” doesn’t have much bearing on the themes of the film as a whole or Worthless as a song.]

So there you have it. “Worthless” is a critical allegory of our self-centric culture that has eschewed traditional norms in favor of a rapidly bloating modernity that invalidates those who we view as different and creates impossible stressors for even those of us who do adapt. All of that disguised as a bunch of cars in a children’s flick.

This song always haunted me a bit as a kid, now I know why. To this day, I think TBLT has some of the best music in an American cartoon produced, ever. Despite the low budget, I think their lack of heavy-handed restrictions allowed them to explore themes and create lyrical exposes that big studious cartoons have yet to catch up with. In fact I recently bought the TBLT soundtrack, I can’t say that for any other cartoon.

-Taco