It’s been awhile since I’ve done a “historical” post here on Dinosaur Bear, and while I like writing them, I generally prefer to do so with some personal context. For instance, my Salem post was pretty much all history, but it was grounded in the fact that I actually went to the place I was talking about. Fortunately, I recently visited another place that has some pretty cool history behind it, so now I get to share that information in addition to talking about actually being there.

This time around the location is the Prospect Hill Monument, located near near Union Square in Somerville.

In some ways this might actually be seen as an intellectual extension of the memorial marker I found way back in November, 2014 and commented on. True to my word (and style) I eventually returned to the area to do some more digging. Of course to give credit where credit is due, Tristen actually served as the impetus for heading up to the “Somerville Castle” or rather “Rastle,” because he wanted to mark something off of our Boston Bucket List this week. So, since it really isn’t that difficult to get to there from where we live, we decided to head up to Prospect Hill on Tuesday.

Since we had started the day off right with some coffee and donuts courtesy of Harvard – and more importantly because the weather was actually nice for a change – we figured it was a good day to visit the Castle, so later that afternoon once SB had returned home and I’d taken care of a few things we headed out.

Of course, us being us, we used this an excuse to go to a new cafe in Union Square that we’d never been to before called Bloc 11. While there I got something very.. er.. interesting.

It might look like iced coffee, and I guess it sort of is, but in actuality it’s a “Coffee Soda” which is espresso with soda water and vanilla syrup. The idea of a coffee soda was so odd that I just had to try it, and yeah, I’m not sure I’d get it again, but I’m still glad I tried it. In case you were wondering, SB got something called a “Lime Rickey” which was soda water, lime juice, and raspberry syrup. It was much more normal – and honestly better – than my coffee soda, though I still have no regrets.

Anyways, about that history.

Prospect Hill obviously predates the Prospect Hill Monument, henceforth referred to as the Castle, and in order to understand why the Castle is there, you first need to understand why the hill even matters (because the are two related – but for separate reasons).

Prospect Hill wasn’t originally known as “Prospect Hill,” in fact my guess is that the animals probably didn’t call it much of anything and instead just nom’d things on it, slept on it, and shat on it. Fast forwarding a bit to when the Europeans arrived (not because the Native American’s didn’t have a name for the hill – they probably did – but I just can’t find it): this hill was given a variety of names such as Strawberry Hill, and later Wildredge’s Hill, but eventually they settled on Prospect Hill at some point during the 18th century. As Somerville proper wasn’t incorporated until 1842, much of the land around Prospect Hill was used for purposes ranging from agriculture to brick making. It was the “rural” area beyond the more populated Charlestown.

Now, this random wooded hill became quite important due to that little series of events we have now come to call the American Revolutionary War. This was in no small part due to the fact that in the era before planes, satellites, and drones, having the high-ground was exceedingly important in armed conflict, and it just so happened that Prospect Hill gave a good view of Boston, Charlestown, the Charles River, Boston Harbor, and even Cambridge. So, like it’s much more famous counterparts Bunker Hill and Breeds Hill, Prospect Hill played an important role in the Siege of Boston from April 19, 1775 through March 17, 1776.

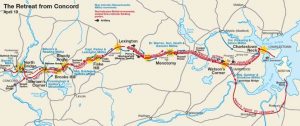

Of this all started with the Battles of Lexington and Concord, and Prospect Hill was right along the Battle Road, which is something I have walked a fair stretch of myself and which is covered extensively here.

In fact, I’m going to continue under the premise that you’ve just read my entire Lexington and Concord post, not because I actually think you will, but because if you’re confused by the following image then you can go figure it out for yourself. 😛

So, as the retreat from Concord was in full swing the British passed through the present-day Union Square area again (excepting retreating rather than advancing this time). You can see their path here, inclusive of Prospect Hill.

Some colonists had gathered near the hill in anticipation of the retreating British – though the hill was not fortified at this point – and when the huge British column arrived it was clear that those who had gathered at the hill were clearly outnumbered and outgunned. However, they did engage the British in a skirmish for a bit before retreating – all but one of them anyways. As the British began to overtake their position the colonists fled, but one of them, 65 year old James Miller stayed behind and said “I am too old to run.”

He fought until he was killed, and become the only known colonial casualty during this skirmish at Prospect Hill. And thus I finally answered some of my own questions from 2014. Of course Miller’s last stand didn’t keep the British from reaching Charlestown, and so the Siege of Boston officially began as the Colonial Army gathered around the outskirts of town. What happened next – not immediately of course, but “next” for our purposes – is that the British scored a Pyrrhic victory at Bunker Hill and forced the Colonial Army to fall back into the surrounding area, most prominently to Prospect Hill.

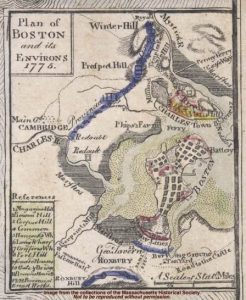

This next image shows the general setup as things started to unfold, with the rough location of the British in red and the colonists in blue (keep in mind that Boston looks essentially nothing like this anymore due to dredging, etc.).

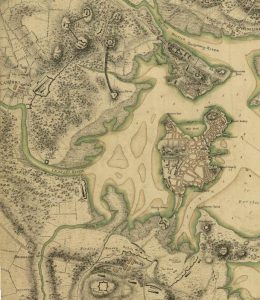

And here is a slightly more geographically detailed view, where you can see the hills the colonists were relying on – inclusive of Prospect Hill – in the upper left portion of the image.

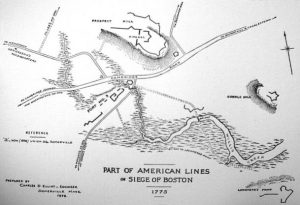

And lastly, a detail of Prospect Hill itself, where you can see the fortifications they put up once they knew they’d be digging in for awhile.

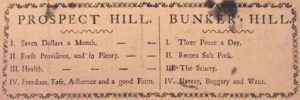

From that point a big sort of “stand-off” occurred between the colonists on the hills in the countryside around Boston, and the British on the hills near and within Boston. In some regards, it came to be viewed as a “Prospect Hill [Colonists] vs. Bunker Hill [British]” affair. In fact, this hill vs. hill battle is believed to be America’s very first usage of military propaganda, with leaflets being distributed to British soldiers which compared the pay and conditions of the Bunker Hill fort against the Prospect Hill fort.

I am particularly fond of Item III, namely that being stationed at Prospect Hill will result in “Health” – with no explanation beyond that, while being stationed at Bunker Hill will get yo’ ass scurvy. I don’t know about you, but I’m willing to bet that “Health” is better than “Scurvy.” Plus Prospect Hill has “Freedom” – the United States didn’t even exist yet and we were already bragging about “Muh Freedoms.”

I don’t know how well the propaganda worked, but if I were a British soldier 3,269 miles from home, the mere chance of not having to eat “Rotten Salt Pork” would have had me defecting so fast that even Benedict Arnold would be jealous.

241 year old leaflets aside, like any siege, the Siege of Boston was long, so each side really entrenched themselves in their respective hills. The result was that a lot of men spent a lot of time on Prospect Hill, with one such example being Caleb Haskell who kept a diary of his time during the war, including his time on Prospect Hill, where he talks about the British shooting cannons, burning things, drinking tea, etc., you know, normal British stuff. It was during this extended standoff that the British came to refer to Prospect Hill as “Mount Pisgah” based on a reading of Deuteronomy 34:1 that has Moses climbing Mount Pisgah to view the Promised Land he wasn’t supposed to enter, e.g., the British viewed Prospect Hill as bit of a problem when it came to getting out of Boston, but at the same time the Colonial Army on the hill couldn’t get in either. In other words, both of them were looking towards something they wanted, but couldn’t have.

And although Prospect Hill was an important location during the Siege of Boston, it probably would have fallen into the pages of history without much fanfare (in the shadow of Bunker Hill – which was actually Breeds Hill) had something not happened there on January 1, 1776.

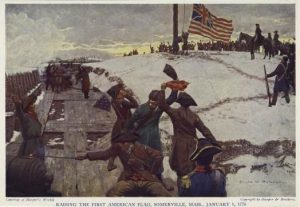

During the siege an ole’ chap named George Washington (who was chilaxing down in Cambridge and whose name I am not going to link to Wikipedia for, because oh my god seriously) would frequently visit the front lines, including Prospect Hill. During one of these visits Washington noticed that the hill not only provided an excellent view of the British, but that it was clear that the British could easily see them as well – and what better way to piss off a world empire than to make your own flag and raise it on the highest point you have. It’s kind of like waving your wiener at them, except even that the biggest of human wieners are too small to see from more than 1.5 miles away, so a flag would have to do. And thus, on New Year’s Day, 1776, the Colonial Army raised the first “Grand Union Flag” which was the first official and true flag of the United Colonies and subsequently the United States of America.

Of course we have no idea what the event actually looked like, so let’s add in George Washington on a horse for style.

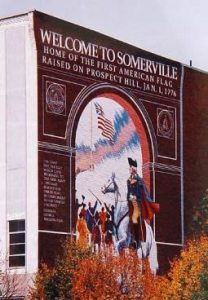

Still, it was a heck of an act and it undoubtedly made the British commanders piss their knickerbockers in rage, though my guess is that the regulars probably were too busy with that scurvy to care too much. Humor aside, the fact that Prospect Hill was pretty much where our first flag flew is a pretty big deal – though oddly it seems to have not fared well against Bunker Hill’s legacy, which is kind of odd considering how much we love our flag. Notwithstanding Prospect Hill’s relative obscurity outside of Boston aside, the hill was an important location during the siege, both for its war-time benefits and also for the symbolism of the flag raising. So, it’s no great surprise that Somerville is quite proud that Prospect Hill is within it’s tourist-grabbing jurisdiction.

But that wasn’t always the case, in fact, after the Siege of Boston had ended and the war was marching into its middle years, Prospect Hill lost a bit of its majesty as it became the location of a Prisoner of War camp for captured British soldiers, and at one point held as many as 2,300 of them after the Second Battle of Saratoga. Once the war ended Prospect Hill was just kind of a muddy mess with abandoned fortifications that had been picked-clean of anything of value. Eventually the fortifications were torn town and trees and bushes and the like reclaimed the hill, and at one point a grist mill operated on the hill and the Tufts family even owned an estate near it, but by and large it just returned to being a plain ole’ hill. And really that could have been Prospect Hill’s fate, to sit for a couple hundred years until Somerville paved over it and put up a parking lot. But, a couple of things happened which saved Prospect Hill from this fate.

For starters, when Somerville was incorporated in 1842 the town fired some cannons from the summit of the hill to celebrate, and also set things on fire, and drank beer, etc., you know, typical American stuff. This at least brought the hill back into public consciousnesses as an important place. Then, when the American Civil War began in 1861 the Union Army cleared a bit of Prospect Hill and used it as a training and recruitment center. In fact, this why Union Square has its name – it was known as Liberty Pole Square prior to the Civil War, but as a display of patriotism and support for the Union troops, it was renamed Union Square, complete with its own little Union camp right up the hill. During this occupation the Union soldiers raised their own flag at the summit, replicating what their revolutionary ancestors had done, though the flag looked a bit different at this point.

Once the Civil War was over the Union packed up camp and left, but their use of the hill had put it back on the map, and by back on the map I mean that people decided to do what people do and build houses all over it. In fact, in order to make Prospect Hill an even more ideal living area they decided to fill in the mostly polluted Miller’s River which ran next to it (filling in water has kind of always been Boston’s fetish). They did so by chopping off the top of Prospect Hill and carting it down to the river and dumping it in there. From there, houses started to dot the base of the hill, and as Somerville became more accessible to downtown Boston – first by horse carriage, then by train, and then by electric streetcar [which I am sure was more reliable than the MBTA] – more and more residents wanted to live on Prospect Hill. Yet, at the same time that the desire to build things was growing, a desire to not build so many things was also growing, and so a conservation society of concerned Somerville residents (e.g. not poor people) banded together and formed the “Prospect Hill Park Association” in the 1890s. Their goal was to create a park for residents to use and also to honor the legacy of the “First Flag” at Prospect Hill. And so they set out to get some shit done, and even gathered over 500 signatures in support of their efforts, which they sent to the Somerville City Council. Upon seeing how upset half the towns rich-folk were, the Council decided that they should probably do something, and in 1898 the new Somerville Historical Society held a “Historic Festival at Ye Foot of Prospect Hill” to raise awareness of the hill’s past and more importantly to raise some more money (because what’s better than 500 wealthy philanthropists? 501 wealthy philanthropists).

After gaining political, residential, and financial support the Historical Society decided it was time to build something at the top of the hill, because who doesn’t like building things at the top of hills. But no simple memorial stone would do, they needed to make something epic for the location of the first flag, so they decided to build a castle, because no one would ever associate a Castle with England, nope.

Here is an early concept sketch from ~1901.

The funny thing was, the tip-top of the hill (or rather, the tip-top after they shaved it off) was still privately owned and there were two houses in the area that was planned for the park. However, that didn’t pose much of an issue as Somerville just “bought” the land (I use scare quotes, but in fairness they probably did pay them market value), demolished the houses, and gave the Historical Society a thumbs up.

That said, the job was far from done, as most of the hill needed to be cleared, smoothed out, and landscaped.

Preparing the hill for the the park and Castle was quite a bit of work, especially since there wasn’t an easy way to get thousands of tons of stones up there.

As a way of rectifying that problem they did what everyone since the Romans has loved to do, they built and expanded roads. One in the front:

And one in the back:

I wasn’t able to figure how how long the project took, but it was no more than 2 years would be my guess, if not less. They completed and dedicated the tower in 1903, and when they did they partied like it was 1776, heck there was maybe even a bit of scurvy in there too.

The total cost of the project was a bit over $8,700 dollars, or in very roughly in modern money about $250,000, which really isn’t that bad considering that if we did the same thing today it would cost like 5 million dollars just to build 10 feet of road.

Speaking of today, let’s jump forward in time to SB and I’s visit – I’m sure you think all this history is great and all, but are probably wondering what things look like today (er well.. two days ago). The answer is that things really aren’t that much different.

The Castle itself is largely unchanged, however you will notice large concrete retaining walls around it now. These were added in 1955 in order to prevent erosion, though the consensus seems to be that the walls were wildly overkill for their purpose. While the concrete doesn’t mesh that well with the castle, I honestly don’t think it looks that bad, and it’s certainly better than the whole thing collapsing down the hill.

In order to get up to the park you can either take a long ramp, or take a more direct series of stairs. Of course in order to get the the stairs and ramp you first have to walk up the base of hill itself, and unless you have a car and are extremely lucky with parking, you’re going to be hoofing that first portion regardless of whether or not you decided to end with the stairs or the ramp.

And although the park is accessible via ramp, the Castle itself requires stairs, so for SB and I it was stairs leading to more stairs.

Though in fairness it wasn’t nearly as bad as I’m making it seem, really only the first stairs on the hill are anything near “strenuous.”

And once you are done with the stairs, you finally make it to the monument itself [or rather Tristen’s Rastle].

The base of the Castle provides a nice view of Prospect Hill Park, which sits on both sides of the monument.

But the real views are to be found when you cross around to the front of the Castle.

Here you can take in views of Cambridge in the Southwest.

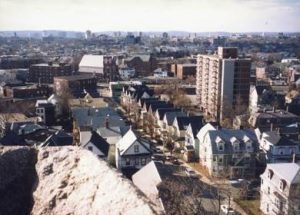

Somerville in the South.

And Boston in the Southeast.

Here is a view of the three together, which kind of lets you see what I saw, just with some added panoramic wonkiness from a cellphone photographer such as myself.

Then, at the top of the Castle is none other than the Grand Union Flag itself, still flapping in that ever-constant Bostonian breeze.

In fact it was a wonderful day to visit, there were blue skies with light clouds, and a nice warm sun.

And while the breeze was (as always) there, it wasn’t quite cold, but had settled in somewhere between “cool” and “kinda-chilly.”

And even this “chill” was really only from the fact that the Castle is so much higher up than the surrounding area, so it just acts as a beacon for all that wind.

Notice the tiny plane, it looks like ants are coming along nicely with their industrial revolution.

If you were wondering about the inside of the Castle, then you are kind of out of luck. At some point since its completion in 1903 people started rampantly suing one another and destroying things for no reason, so now we can’t have any fun and thus the doors are locked tight.

From what I can tell there are only a handful of times each year that it’s open to the public, and of those the only one I was able to actually pin down was the annual New Year’s Day celebration where they reenact the flag raising, complete with a procession and traditional attire, dance, and food. Of course this was most assuredly not New Year’s Day, so SB and I were locked out (though the boys still managed to get inside, to no one’s surprise). However, I did find a few photos from inside and on top of the tower. Here is a shot in the lower interior:

And here is an older shot from the top of the tower while facing towards Somerville (and Cambridge in the distance):

And another older shot from top while facing towards Boston.

And although SB and I couldn’t go in or up the tower, we still really enjoyed the views from the base, be it of Prospect Hill Park itself:

Or of the cityscape surrounding us:

Even in spite of the drastically changed landscape and city, not to mention the addition of about 3 or 4 million people, you can still imagine how much of perspective Prospect Hill offered the Colonial Army, and inversely how frustrating it probably was for the British since their enemy could see just about everything there were doing. Prospect Hill captured pretty much all of it, from troop movements into and out of Boston, to naval movements, to excursions up the Charles River, the colonials could see it all, so, it’s no great surprise that it was chosen as the location to raise our first true flag.

So, what lies in store for the “Somerville Castle” in the future? Well, despite having an important role in the birth of the United States it has suffered the same fate as a lot of historical sites and has fallen into a bit of disrepair. It’s not really in “bad shape” per se, but it does need to some TLC. In fact recent reports have estimated that the Castle itself needs somewhere between $400,000 and $900,000 to repair – keeping in mind that the whole thing took only ~$250,000 in modern dollars to build (like I said, the $8,700 wasn’t bad). Unfortunately, it’s not quite as simple as throwing a party and raising all that money anymore, so I don’t know if there are any current plans to repair everything. That said, given how the greater Boston area thrives on its history, I have no doubt that the Prospect Hill Monument will get the repairs it needs eventually, but for now we just have to appreciate it as it currently exists, which I am sure is a whole hell of a lot better than the conditions of the hill back in the winter of 1776.

As we walked back down the hill to Union Square, I was reminded of how fortunate I am to live in someplace surrounded by so much history, and while I definitely don’t see myself staying in Boston very long after law school, it’s the little side trips like this that have come to make living here some an awesome experience. That, and cool little knickknacks like this pinwheel that was next to the bus stop.

Until next time,

-Taco

P.S. I must acknowledge the gracious assistance of King Tristen for helping me do research on his Rastle, as well as for allowing me to write about his Rastle in the first place.