Hello and welcome to Dinosaur Bear!

It’s been over 3 months since my last Spring-related post and Spring has definitely come and gone. I think I had a few ideas for posts after that, but things got very busy for me. I’ve had some smaller adventures in my absence from blogging, though nothing as large as Southeastern New Mexico and California. The busyness, however, has largely come from lawyerly-related things. That said, what I wanted to discuss in this post is my recent voyage through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven – courtesy of Dante Alighieri and his Divine Comedy.

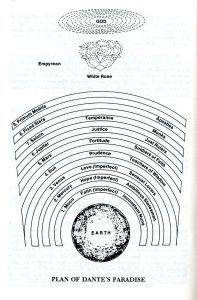

A depiction of Dante and the various aspects of his Divine Comedy – this picture will make more sense after you’ve read this post.

In fact, this is probably the first post dedicated to literature that I’ve ever done on Dinosaur Bear and as such I’ve decided to make a special new category for it, aptly titled “Literature.” Before we get into the nitty-gritty of the Divine Comedy, I’ll first say that I do not intend for this to be a formal book review or some scholarly inquest into Dante’s work. First, despite being decently well read I’m not qualified to act like any sort of authority on Dante, second, I don’t really want to review the work in a more substantive sense, and instead just want to talk about my own experiences with it. For purposes of organization (which as you’ll shortly learn I think Dante would appreciate) I’ve divided this post into three parts. Part 1 deals with the “What” of the Divine Comedy, that is, what is it and, to a lesser extent, who Dante was. Part 2 deals with the “How” of the Divine Comedy, specifically how I think you should go about reading the poem. Part 3, the final part, deals with the “Why” of the Divine Comedy, that is, why I feel like you should read it and why it moved me to create this post.

Part 1 – “What” is the Divine Comedy?

So with that said, just what is the Divine Comedy? Well, while you’ve probably heard of “The Divine Comedy” before, if you haven’t then I’m almost positive you’ve heard of “Dante’s Inferno.” Inferno, however, is just one of three parts of the larger Divine Comedy. The Divine Comedy is a poem composed by Dante Alighieri between roughly 1308 and 1320. The Divine Comedy is one monster of a poem, consisting of 100 cantos (to keep things simple, think of these as chapters), divided over three cantiche (to further keep things simple, think of these as parts or books): Inferno (Hell – 34 cantos), Purgatorio (Purgatory – 33 cantos), and Paradiso (Heaven – 33 cantos). The poem spans 14,233 lines and is considered by many to not only be the preeminent work in Italian, but one of the (if not the) finest pieces of literature ever made in the entire world. It’s worth noting here that Dante himself did not refer to the poem as “The Divine Comedy” as there is a bit of pomposity about that if you really consider it (though Dante was, in many ways, quiet full of himself [endearingly so in my humble opinion] though I’ll get more into that later). It wasn’t until over 150 years after Dante finished the poem (and obviously long after Dante’s own death) that people started referring to it as “The Divine Comedy.” Instead Dante simply titled the poem Comedìa, which was specifically Tuscan, and meant “Comedy.” This rather mundane title was wholly intentional and reflected the classic concept of a “Comedy” – as opposed to a “Tragedy.” If you are unfamiliar with what those terms traditionally meant in this context, I’m sorry to say that Comedy isn’t what you might expect if you get your culture from contemporary television (though to Dante’s credit, a few parts in the Divine Comedy did make me literally laugh out loud). Instead a Comedy – loosely construed – was just a story that started at a low point and ended at a high point. This is figuratively speaking (e.g. a “happy ending”) though in Dante’s case it was also literal. A Tragedy, by contrast, was the exact opposite: a story that started high and ended low.

In every sense of the term (in that context) the Divine Comedy was most certainly a story of upward motion, both figuratively and literally. The “Divine” was added to the poem based on its context and has since become the most common title of the poem (if not in the academic circles which surround the study of it and Dante’s other works). So, if you hear of The Divine Comedy, the Divine Comedy, Divina Commedia, Commedia, or Comedìa you’re hearing of the same work. If you’ve heard of the most popular portion of the poem, Inferno, i.e. “Dante’s Inferno” then you’ve heard of the first part of the work. For the purposes of this post, I’m just going to refer to it as the “Divine Comedy,” but I did want to share a brief recap of what the title originally was (and arguably still is).

Before diving into the Divine Comedy, let’s briefly touch on the man behind the poem.

Dante Alighieri (henceforth just Dante), was born circa 1265 and died in 1321 (just one year after finishing Paradiso, the final portion of the Divine Comedy). He was born in Florence and died in Ravenna – both cities in what what is now the modern country of Italy. His life is worthy of not only an entire blog post, but multiple books have been dedicated solely to the subject. As such, I can’t possibly hope to adequately delve into his relationship with the Holy Roman Empire, the Church, Florence, or even begin to scratch the surface of the impact of the Guelph and Ghibelline conflict that shaped most of his life. Dante’s life is one of politics, faith, and literature (with the order of those three things shifting depending on the point of time in his life you examine). The larger theme of this post is that I want you, implore you in fact, to read the Divine Comedy – and I’ll recommend a particular translation in a bit. If you choose to read it and listen to my recommendation you’ll learn all you need to about Dante the man in order to contextualize the when/where/why of his writing the Divine Comedy. For now, just know that Dante – despite the overt and initial appearance of the Divine Comedy as an exclusively religious work – was just as entrenched in the political world of his time as he was the spiritual.

Now, with a cursory idea of who Dante was, let’s exam his most famous (but far from sole) work, the Divine Comedy.

A depiction of Dante’s Hell – this too will make more sense once we get into the details of Inferno.

The Divine Comedy is, simply put, Dante’s reflection of a voyage from Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven – as reflected by beliefs (both personal and widely held) of 13th and 14th century Italy. What’s key about this voyage is that Dante writes it as thought it actually happened. Yes, the poem is a recollection – not some fable. This means that Dante joins the likes of Paul as the only still-living mortal to journey to Heaven and come back. You can see why this might have caused a stir at the time, and it is reflected in Dante’s carefully crafted approach to the entirety of his experience. If tomorrow I decided to claim that I’d been allowed to traverse Hell, Heaven, and Purgatory – and look at God, people would, at worst, just think I was a loon. In 1320 though such claims were much more risky. So from the outset, Dante is on thin ice, and that he deviates from popular notions at several points during the poem is only further proof of the risks Dante was willing to take in composing it. That Dante specifically calls out regions, cultures, institutions, and specific people that he either hates or adores in the poem, only adds to his convictions. You know that politician you don’t like? Have you ever thought about them burning in Hell? Dante did, and he wrote an entire poem about it – back when people were still getting executed for funsies. Dante spared no one from his ire – not even Popes. Yet, at the same time, Dante also bestows God’s grace on this people he did view favorably – and sometimes even allowed people he didn’t much care for to win the afterlife lottery (Dante wasn’t all vengeance, after all).

The point here, is that while Dante did set his (to be believed as factual) voyage in the realms of Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven, he didn’t hedge his bets by wholly disassociating these places from mortal realm. Nope, Dante stocked these places full of all sorts of actual people, famous or otherwise. While I won’t get much into specifics here, you have to realize that it’s entirely possible that someone opened up the Divine Comedy in 1320 and found themselves burning in hellfire. While this probably wouldn’t gain you many friends today, in 1320 this was an even bigger deal.

As Dante (the protagonist and thus the author) moves through this voyage, he is guided first by the Roman poet Virgil, then by Beatrice, and finally (and most briefly) by St. Bernard (Bernard of Clairvaux, not the dog). While I’m doing a disservice by not discussing each of these guides in depth – especially my man Virgil who is probably the most tragic figure of the entire poem – I’m going to gloss over them a bit simply because each of them could serve as an entire blog post (or book, which as happened with at least Virgil and Beatrice, if not Bernard too). Virgil guides Dante through Hell (Inferno) and most of Purgatory (Purgatorio), Beatrice guides Dante through the last part of Purgatory (technically Earthly Paradise/The Garden of Eden, but still within Purgatorio) and most of Heaven (Paradiso) and Bernard guides Dante through the final part of Heaven. Each guide represents specific things for Dante (especially Beatrice) and both Virgil and Beatrice are deeply, deeply influential in the course of the Divine Comedy and arguably Dante’s actual life. Here, I take the “easy way out” by only mentioning that they serve as his guides, and leave the real meat of the matter to you in your own readings should you (rightfully) choose to read the poem.

So, as we change now to looking at the specific parts of the Divine Comedy, just remember that Dante would have us (the readers) believe that the entire poem is a literal truth and that Dante fills its pages with real people and that he is always with at least one major guide (and occasionally they are joined by secondary ones). I’ll first discuss the basic structure of each part of the poem and then get into my thoughts about the Divine Comedy as a whole.

The journey begins in Hell, or Inferno.

“Midway in the journey of our life

I came to myself in a dark wood,

for the straight way was lost.”

So begins Inferno and thus the Divine Comedy itself. I first started reading Inferno while I was on a plane ride out to see Meem and I knew from those very first lines that I was going to be hooked. My enthusiasm for Inferno didn’t wane, and I worked my way through the first part of the Divine Comedy at a rate of one canto (again, for simplicity’s sake: chapter) per day. In Inferno Dante “awakes” and finds himself at the edge of Hell, specifically in a “Dark Wood.” From here Dante begins his voyage through Hell where he meets up with Virgil and proceeds downward into the abyss. As Dante passes through the gates of Hell, he reads the inscription, one line of which which I am almost positive you are all familiar with. In truth that line (bold text below) is just part of the larger inscription over Hell’s gate, which reads in full:

“Through me the way to the city of woe,

Through me the way to eternal pain,

Through me the way among the lost.

Justice moved my maker on high.

Divine power made me,

Wisdom supreme, and primal love.

Before me nothing was but things eternal,

And I endure eternally.

Abandon all hope, you who enter here.”

Like Purgatorio and Paradiso that follow it, Dante’s Hell in Inferno is very organized. If you’ve ever heard someone say something along the lines of “They deserve to rot in the X circle of Hell” (or some variant thereof) then you’ll know where this is going. Dante’s Hell is divided into Circles (or Layers) each corresponding to certain kind (or kinds) of sin/infraction. There are generally agreed to be 9 Circles, though certain scholars also include a “Circle 0” which is sort of the prelude to Hell itself. In the translation and commentary I read, the Circles of Hell are defined as follows:

Circle 0: The Neutrals

Circle 1: Limbo (note that in Dante’s theological construction Purgatory and Limbo are very different things – I’ll discuss this more below)

Circle 2: Lust

Circle 3: Gluttony

Circle 4: Avarice & Prodigality

Circle 5: Anger & Sullenness

Circle 6: Heresy

Circle 7: Violence (This Circle is divided into tiers: against others, against self, and against God [itself further divided into various tiers])

Circle 8: The Ten Malebolge (The Circle is devoted to a myriad of ten sins ranging from diviners to simoniacs to barrators to thieves)

Circle 9: The Frozen Floor of Hell (This Circle deals largely with various types of treachery and betrayal, with the worst being against “Rightful Lords” or “Benefactors”)

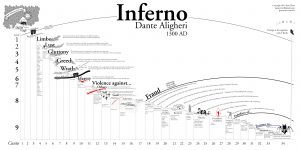

What I didn’t know is that a lot of the precise “titles” of these circles are a matter of interpretation and debate. So while one source may refer to Circle 5 simply as “Anger” others will include “Sullenness.” The deeper one gets into Hell, that is, past Gluttony (Circle 3) the more varied one will find the interpretations to be. Most of this stems from the fact that while Dante made some things very overt, he made other issues much for difficult to discern or simply left the matter unanswered (and thus subject to literally over 700 years of debate). Here is one version of a map of Dante’s Hell I found. I did not make this map, all credit goes to the creator whose information can be found in the upper right corner of the image. You’ll want to click to make it larger – I did not compress this map (or any of the informative photos in this post for that matter). You’ll notice some variations between what the creator has listed and what I have listed above. While the general flow is generally the same, I thought the differences between this map and my sources was a good example of how complex Dante’s Hell is. Plus it’s a really cool map in general.

After Dante and Virgil make their way through Hell, encountering both expected and unexpected subjects, as well as a myriad of Demons and even an Angel or two (not the fallen Angels, but still-divine Angels – Hell is God’s domain after all), the boys meet Lucifer himself. Dante’s take on what “the devil” actually embodies is quite interesting, as it is simultaneously an image of the once-beautiful fallen son of God, Lucifer, while also being something a bit more abstract and inward looking (“The devil is not as black as he is painted“). I’m not going to spoil much about the specific details of the Divine Comedy, because again I’m hoping you’ll read it for yourself, but to say that Inferno has one hell (ba dum tiss) of an ending is not an understatement.

After emerging from Hell – a scene which I’ll discuss more in a bit and which I consider to be one of the most profound moments in my entire life as a reader – Dante and Virgil make their way to next obstacle: the Mount of Purgatory.

Their journey continues in the second cantiche (i.e. book): Purgatorio.

“To run its course through smoother water

the small bark of my wit now hoists its sail,

leaving that cruel sea behind.

Now I shall sing of the second kingdom,

there where the soul of man is cleansed,

made worthy to ascend to Heaven.”

Thus begins Purgatorio – with the protagonist (i.e. Dante) and Virgil making their way to the base of the Mountain of Purgatory. Here I should probably take a moment to ensure everyone is on the same page as to what Purgatory meant for Dante, as I’ve elsewhere noticed some confusion in the discussion around “Limbo” versus “Purgatory.” In Dante’s world (both within the world of this, his poem, and also his actual world (e.g. 1200/1300s) Limbo was a place in Hell. In Limbo you, in the words of Virgil (a resident of Limbo), are punished by being forced to live without hope, yet to live on in desire. That is, you spend eternity with desire for salvation, yet knowing it’s not going to come (save specific divine intervention, such as the Harrowing of Hell). Unlike those lower down in Hell, the residents of Limbo were not dire sinners, they were simply guilty of not believing in the Christ to come, or revering the Christ already born (and died). Pretty harsh for those “virtuous pagans” (Dante’s words) who were legitimately good people and yet, by the situation of simply being born before Christ – and not, somehow, having faith in his eventual arrival (as did many of the significant earlier Hebrews, etc.) – you’re doomed to Limbo. Even better, unbaptized babies end up in Limbo too. This is part of the “tragedy” of Limbo (and Virgil is the figurehead of this theme in the Divine Comedy) and while Dante doesn’t bend the rules (at least not on this particular issue) he also isn’t really comfortable with them, as he takes doubts about such inhabitants as the infants all the way to the Kingdom of Heaven.

So, Limbo does not imply that you are actually “fluctuating” between damned and saved, you’re damned, and lest some direct act of God happens (see again the Harrowing) you’re stuck in Hell. Now, Purgatory is different. All souls in Purgatory are on the route to salvation, or, put differently, they are already “saved” in the sense that eventually (and eventually can be a very, very long time in Dante’s Purgatory) they will make their way to Heaven. In order to reach Heaven, however, they need to purge the remnants of their Earthly sins and desires and prepare themselves – through suffering and torment (though of a much different kind than the damned in Hell are suffering) – to enter Paradise. Since Dante was a very organized man who – like yours truly – values a good structure, the Mount of Purgatory is divided into seven Terraces, each devoted to a particular kind (or kinds) of sin. However, much like Hell there is actually a “pre-Purgatory” – more commonly referred to as “Ante-Purgatory” that one must pass through before getting to Purgatory proper. This “Ante-Purgatory” involves a lot of waiting, though the precise time for each person is variable. This waiting involves first simply waiting on the boat (piloted by no less than an Angel) to take you to the base of the Mount, then waiting further outside the gate of Purgatory proper depending on whether you were an excommunicate or a late-repentant (that is, you waited until way late – sometimes the moments prior to death – to make good with your broseph God). Once you’ve waited out all that (and Dante has precise formulations for such waits) then you actually get to pass through the Gate of Purgatory and start your way up the mountain via the Terraces. The Terraces in Dante’s Purgatory are as follows (structured from lowest to highest):

Base (ante-purgatory)

First Terrace – Pride

Second Terrace – Envy

Third Terrace – Wrath

Forth Terrace – Sloth

Fifth Terrace – Avarice & Prodigality

Sixth Terrace – Gluttony

Seventh Terrace – Lust

Peak (Earthly Paradise, i.e. the Garden of Eden).

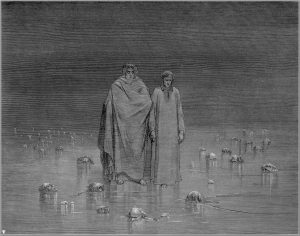

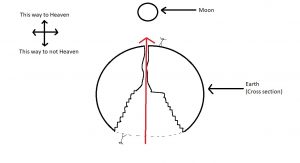

While this depiction has the mountain looking much smaller than Dante depicts it and doesn’t label the Terraces, it does give you and idea of how Dante envisioned the place, albeit on a micro easier-to-draw scale.

As Dante and Virgil move up the mountain they continue to meet people Dante knew previously (either directly or indirectly) in addition to encountering the various trials and tribulations that God placed on the Mount to “purge” the repentant as they moved closer to Heaven. Now, here it should be said that Purgatory is nowhere near as dark and torturous as Hell, but that isn’t to say it’s all sunshine and roses either (save for the top of the mountain, that is). In fact many of the residents of the mountain are not in a great place, though as Dante points out, despite their suffering they still know they’ll make it to Heaven eventually, so in that way they are better off than any on Earth.

The “punishments” of those on Purgatory – like the more sinister punishments of those in Hell – vary according to the sin and the weight of their particular sinning. One may find themselves carrying immense wait, being forced to run endlessly; being subjected to insatiable hunger, or – oddly enough considering the whole Hell thing – burning in fire. Either way, the residents are always working closer to God as they progress up the mountain. Dante and Virgil just progress much more quickly. Eventually they meet Statius, who is basically the founding member of the Virgil fan-club, a soul who just so happens to be granted access to Heaven at the same time as Dante (though Statius’s stay is permanent, Dante is just visiting this time around). Before too long the trio make their way to the top of the mountain, Earthly Paradise, home to Adam and Eve’s infamous screw-up (Dante even encounters the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil itself [he also encounters offshoots of the Tree of Life elsewhere in Purgatory]). Here Virgil is forced to return to Limbo after babysitting Dante (my bro Virgil doesn’t even get a merit badge for this crap) and Beatrice takes over as Dante’s guide. From there the pair proceeds on to Heaven itself, or the version of it that was dominant during Dante’s time – a version which, especially with Dante’s own added twists, is probably not how you imagine Heaven, if you imagine it at all.

Having passed through Hell and Purgatory, Dante now makes his way to: Paradiso.

“The glory of Him who moves all things

pervades the universe and shines

in one part more and in another less.

I was in that heaven which receives

more of His light. He who comes down from here

can neither know nor tell what he has seen,

for, drawing near to its desire,

so deeply is our intellect immersed

that memory cannot follow after it.”

These are the opening tercets of Paradiso, and if they sound a bit more complex to you than those which started Inferno and Purgatory then you’ll find yourself in the company of yours truly as well as a large contingent of other readers. Paradiso is by far the most complex of the Divine Comedy’s three cantiche, but I’ll touch more on that below. While the substance of Paradiso is extremely theological and philosophical (almost oppressively so at times) the basic structure of Dante’s ascent into heaven will be quite familiar to anyone who has followed his journey through Hell and Purgatory. Dante enjoys his “layers” and so too is this reflected in Heaven, though this time he has structured them as “spheres” with the majority of them being literal spheres in that they are planets. Here’s where Dante’s and 1200/1300’s idea of Heaven probably (though I would never be so brash as to definitively assign you a vision of Heaven) deviates from yours. Do you consider the Moon to part of Heaven? Dante did. Before diving into the spheres of Heaven, let’s briefly recount the overall movement of the poem. Dante started in Hell, he worked his way deeper into Hell, which was also moving closer to the spot where Lucifer fell from heaven and got stuck in the Earth. So while Dante was moving down, he was also moving up. Because this is hard to wrap your head around even when reading the poem, I’ve used my PhD in Microsoft Paint Studies to visualize what I’m referring to.

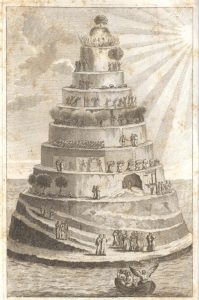

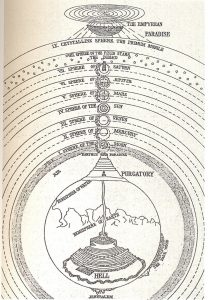

In the above photo, the red arrow represents Dante’s path. The stick figures represent people standing right side up on their respective sides of the planet. As you can see, it is at the “deepest” point of Hell that Dante actually “flips” and becomes right side up, and then eventually emerges near the base of Mount Purgatory (which is not depicted in my above masterpiece). From there he climbs that mountain and begins to ascend further into Heaven. So, despite going “down” into Hell, Dante is in fact continuously moving closer to God’s crib in the Empyrean (more on that in a second). Here is a depiction (not my own) of how this all fits together. If you were to insert my soon-to-be-considered masterpiece of MS Paint above, it would be in the lower portions (i.e. Earth) of this next image.

So now that we have a better idea of the “big picture” so to speak, let’s dive into the “spheres” of Heaven. They are, in ascending (i.e. getting closer to God) order:

Moon

Mercury

Venus

Sun (Yes, the sun was considered a “planet” in this context)

Mars

Jupiter

Saturn

Starry Sphere

Crystalline Sphere

Empyrean

You’ll notice that the order here is a bit different than what you might remember from the last time you looked at a map of our solar system. Keep in mind in Dante’s time the popular belief was still an Earth-centered one, and also my man Dante literally visits the Sun and doesn’t burn into non-existence, so you need to have some faith.

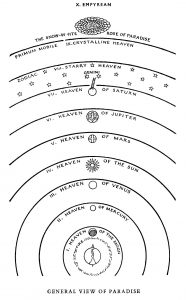

Now, much like the Circles of Hell or the Terraces of Purgatory, these Spheres correspond to certain things, though deducing those “things” is even more complex than in Inferno and Purgatorio. This next photo gives you a general idea of the kinds of people Dante meets in each Sphere and the type of virtue evoked, but delving into these – at times heavy-handed – manifestations of theology and philosophy is beyond the scope of this clearly non-academic blog post.

As Beatrice guides Dante closer and closer to God, Dante meets a myriad of saved souls who expound on one thing or another, all while Dante (who, if you remember, is here in the living flesh – only the second mortal human ever to do so) struggles with the brilliance (literal and figurative) of Heaven itself. Dante is exposed to a great many truths as he traverses the spheres, ranging from the composition of planets, to the connection between forms of matter, to the hierarchy of the Angels. I found discussions of Angelology to be incredibly fascinating. For instance I knew about the Seraphim, but I didn’t understand that there were a myriad of other types of Angels and that Archangels were in fact much lower down the hierarchy than I had previously imagined. For Dante the Angels are structured as thus, listed in order of descending hierarchy (i.e. the Seraphim are the highest tier):

The First Triad

Seraphim

Cherubim

Thrones

The Second Triad

Dominions

Virtues

Powers

The Third Triad

Principalities

Archangels

Angels

Each tier of Angel has a specific series of tasks or relation with God. If you’re interested in learning more about each kind of Angel, you can click their respective names. Eventually, after traversing large swaths of the Heavens and near the very end of Dante’s voyage, Beatrice resumes her spot in the Empyrean, and St. Bernard takes over as Dante’s brief and final guide. The Empyrean, or the Highest Heaven, is where Dante is granted the ability, by no less than Mary herself (after the invocation of all in Heaven on Dante’s behalf) to briefly look upon God.

Now, to discuss God would be the equivalent of ruining the ending of a movie, so you’ll find no such description here. Instead you’ll need to read the poem yourself, and honestly that will make the climatic vision of God all the more powerful. For my part, I found it a fitting end to Dante’s divine journey.

Part 2 – “How” Should you Read the Divine Comedy?

So, we’ve now discussed – at a rudimentary level but a level nonetheless – Dante’s voyage through Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso. I’ve given you the general structure, but left out much of the pivotal details and nuances that have led many to consider it the greatest piece of literature ever written. As mentioned at the outset, that was sort of my goal, to give you enough meat to be interested in reading the poem yourself, but not so much meat as to “spoil” the experience. Now, I’d like to shift into how I’d recommend reading it.

It would be easy to find the text of the Divine Comedy as it is well, well within the public domain after all. It’s available online in various formats, most free, and in print in various formats. You can digest the poem line by line, canto by canto, or if you’re really industrious try to read the entire thing in one setting (though I am not alone in saying that to do so would be a horrible choice and you’d be reading the poem for the wrong reasons). However, what I would instead recommend is for you to not read just the poem, but to instead look to a guide (much as Dante himself did) to assist you through all 14,233 lines of the poem. The best way to do this, absent an actual teacher, is to read the poem via a commentary – and there are a lot of them, going all the way back to just shortly after Dante’s death (though you’ll need knowledge of far more than modern English to read most of them). If English is your most comfortable language, I’d recommend a recently (in the sense of recent vis-à-vis Dante) translated English version. Do I have a particular recommendation? Why yes I do! I recommend the Hollanders’ translation, which is a combination of a proverbial mountain of previous translation efforts and academic commentaries all neatly compiled into a series of three books by Robert and Jean Hollander, with their own added commentary cataloguing and describing not only Dante’s poem, but the scholarly and linguistic efforts that have surrounded it.

I came to the Hollander edition several years back when I decided to read Inferno (which Meem bought me and then which sat on a shelf or in a box for 8 or 9 years). Originally I only really intended to read Inferno (more on that below) but before I had even finished Inferno I looked and found that the Hollanders had editions of both Purgatorio and Paradiso as well, with their editions being published between 2002 (Inferno), 2004 (Purgatorio), and 2008 (Paradiso). Here is a photo of all three books.

Here’s a side shot to give you an entire of just how much material each book consists of in addition to the poem itself.

It might seem a bit odd to suggest you read that much to appreciate the poem, which, while long at 14,233 lines is no where near three hefty books in length. However, the reason I really recommend the commentary approach is threefold.

First, Dante is not always the most straightforward of fellows. He often describes things in extremely roundabout ways. As an example of how this plays out. Imagine that there is a “Bob.” Bob’s full name is Bob Boberton. If I were to tell you something about Bob Boberton, I might say “You know Bob Boberton? Well he bought a new car.” Dante often eschews this approach. If Dante wanted to tell you Bob Boberton bought a new car it might read like this: “The man who resides at the fourth quadrant of the street named for the lilacs that bloom on the southeastern side of the mountain upon which Apollo resides, acquired, in the time when Pisces shines down at a angle which Euclid celebrated, purchased from the trader who scorned the institution in Naples and instead chose the path of a trader in those objects which bear man across the planes, a particularly noteworthy piece of property that shunned the previously commonplace notations of the town nestled beneath the forest where Hermes did instruct the wind.” If you are like me, you’re going to read that and I have no freaking idea who in the hell Dante is referring to, let alone that he bought a car. 700 years of scholars have (mostly) figured this stuff out for you and they can explain it for you. The Hollanders generally do so quite well.

Second, even when Dante is clear and gives specific places and names, you may have no idea who, where, or what he is referring to. Keep in mind Dante wrote this for his audience at the time, not for us 2019 folk. What was widely accepted knowledge and pop culture of 1300 isn’t necessarily so in 2019. Here, again, you can leave it to scholars to explain what in the world Dante is talking about – and even more specifically, explain why that particular person is significant here. Further, there are times when even the scholars don’t quite know what Dante was going for (because Dante was a sneaky dude, very smart, but sneaky) and the Hollanders make even the gaps in knowledge clear.

Third, portions of the Divine Comedy are just downright complex. I’m not talking about the beating around the bush of naming “Bob” as described above, but I mean deeply complex theological and philosophical questions and explanations. This really picks up in the later parts of Purgatorio and is scattered throughout Paradiso (if you’ve ever wondered about why the Moon has dark spots, my guess is that Dante’s explanation would leave you even more confused absent the commentary you’ll miss if you just read the poem). The commentaries provided by the Hollanders generally, though not universally, help explain these deep bits. There more than handful of times I had to consult Google in addition to the Hollander text in order to understand what in the name of Jebus Dante was going on about, but the commentary at least got me started, whereas absent that much I don’t even know if I would have known what to search the internet for.

So, I’d definitely recommend getting a physical copy of the poem and I’d specifically recommend the Hollanders’ books. I like that they keep the original Italian on one page and then the English translation on the opposing page (the commentary follows at the end of each canto). It allows you to both follow along in modern English, but also see the original text at the same time (though there are debates about what Dante actually transcribed [this was via hand, after all] in a few areas, and the Hollanders are good at pointing these spots out). Insofar as the Hollanders’ commentary goes, it is excellent on the whole, but I felt like it borderlines on pedantic at times. The vocabulary seems pleonastic (hypocrisy intended) in many spots and there are some areas in which the reader is presumed to have a pre-existing knowledge about something (especially mythology) that I think is bit over the top. The Hollanders’ also are clearly very interested in certain parts of scholarly debates around the poem that I found a bit dry. For instance, the commentary might got into a two or three page long discourse on how scholars argue over whether Dante meant this or that – when referring to the spelling of a single word, then only have a 4 sentence gloss (and the Hollanders love to use the word “gloss” I bet it appears 500+ times) on something that left me confused and subsequently needing to search the internet. That said, I still heartily recommend all three of their editions, and while the presentation of the commentary skirts the perimeter of the Ivory Tower at times, it is clear that the Hollanders are deeply knowledgeable on all things Dante and the Divine Comedy. Their expertise cannot be substantively challenged in my humble opinion.

I ordered Purgatorio and Paradiso from Amazon and my guess is that is where Meem got Inferno from. I was not at all pleased with Amazon’s handling of the two I ordered as both were damaged on arrival, to the point that pages fell out of Paradiso and I had to glue them back in myself. So Amazon sucks, per usual, but I do recommend these particular books. They are again by Robert and Jean Hollander.

Part 3 – “Why” Should you Read the Divine Comedy?

Now for the most personal part of the post: why I, Señor Taco, was moved enough by this poem from 700 years ago that I wrote an entire post about it. Well, the main reason is again to suggest that you read it yourself. But why do I feel that way? For starters you can argue that as an indisputably important piece of world literature, you’re doing yourself no favors by not reading it. Even if you remove the religious element from it (though as discussed above the poem is just as much political as religious) there is still value in reading great literature. Plus, given how profound an impact the poem has had (a lot of the popular notions of Hell derive from it) you’ll be gaining a deeper understanding of a work which quite literally shaped scholarly and theological discussions of its subject-matter. However, you might be thinking, yes that’s all well and good but I don’t see a several thousand word long Dinosaur Bear post about how I should read The Red Badge of Courage or Ulysses. That’s very true, and that’s why I’d like to close out this post by sharing how Dante’s journey became my own journey, and how I think his journey will appeal to most anyone who devotes the proper amount of time and mental resources to following in his footsteps.

For starters, despite the periods of woe, despair, and anger that dot the poem, the entire journey is – on the whole – one of upward movement and hope. Yes, there are indeed visages of Hell itself and the suffering therein, with Dante dealing with many of these first hand – though under Virgil’s (and more importantly God’s) watch.

Dante and Virgil being accosted by the demons of Hell. Alternate title: two prospective buyers roughly three seconds after stepping onto the used car lot.

As Dante progresses from the abyss of hell and leaves all the monsters (literal or human) therein behind and enters Purgatory, there are certainly moments of despair (often focused on how man is ruining all the chances God gave him on Earth), but it’s still a path of redemption. Much as the path to “recovery” is best viewed as a roller-coaster, so too is Dante’s voyage to God best seen through the imperfect lens of man – a view which only highlights God’s love for the ever-contrarian creature he made in his own image.

Dante speaking with the denizens of Purgatory while Virgil gives him the “Bro seriously God said its my turn to play the Xbox” look.

As Dante approaches God, you feel yourself drawn and moved by his own voyage. Now, I’m not saying this poem is a way to “find God” (though more than a few have claimed that the Divine Comedy brought them to Christ even after the Bible itself had not) nor am I saying that that should be the goal in reading it (though if it is, then more power to you). Instead what I’m saying is that more so than anything else I’ve read, the Divine Comedy is a poem of growth. While for Dante God was God, God can just as easily represent a more “mundane” personal goal or idealized self. That’s the glory of the Divine Comedy, it is most definitely a political and religious poem by a one Dante Alighieri which was written for a very specific set of reasons, but Dante’s writing is so spectacular that the structure of the story and its cast of characters can come to represent hope for almost anyone who reads it. I dare say that even a bonafide atheist (at least those who don’t spend all their time writing angst-ridden posts on questionable sectors of the internet) would find great value in reading the Divine Comedy. I further believe that most spiritual and religious people would find value in it, even if you are far removed from the Christianity that shaped Dante’s world. Now, that said, there are aspects of the Divine Comedy which will probably strike some of faith quite negatively, for instance Dante places Muhammad in Hell – and not only does he place them there, he depicts him as suffering a very bad fate (being that Muhammad was, in Dante’s eyes, little more than a schismatic or heretic). So I don’t mean to sugarcoat away the vehemently Christian structure of the Divine Comedy. However, what I do mean to argue is that even if you find portions of Dante’s vision to be deeply flawed or offensive, that there is value in the journey as a whole.

Further, it’s important to note that Dante himself was uncomfortable with much of what he saw (remember, that since we are to believe that this was a real voyage that Dante is in effect, merely a messenger). For instance, Dante seems quite bothered by some of the rules of Limbo as applied to people who committed no sin other than failing to know Christ (and specially those who were truly virtuous souls, i.e. the virtuous pagans) or why some infants are residing with God while others are stuck in Hell forever. Further, Dante can’t help but be confused as to why Christ saved some from Hell, but not others. Nor does he blindly accept the “sentences” of Purgatory. In fact, Dante even fails to understand some of the workings of Heaven itself. Dante’s voyage also addresses questions such as “What if you love someone, but know in your heart of hearts they deserve to go to Hell for what they’ve done?” or, conversely, “What if you get Heaven expecting to find a lost loved one, but it turns out the they aren’t there?” Neither of these are easy topics, but they work their way into the fabric of Dante’s journey in one format or another. Now, as he achieves harmony with God some of Dante’s inquires are ultimately given the (often muttered here on Earth) refrain of trusting in God’s wisdom, but there is a certain unease even in these moments (if not in the protagonist himself, but almost undoubtedly in the reader).

This is to say that, much like Dante the man, the journey is itself imperfect. Yes, it is guided by a perfect hand (i.e. God), but Dante’s voyage, our voyage, is rendered imperfect by the very fact that we are humans. Yet, despite our imperfections, we are capable of boundless glory through hope. This is where it becomes easier to extrapolate one man’s supposed divine journey to the more “mundane” and “earthly” life of a reader. For instance, if you have something you are struggling with, there is a good (even a great) chance that you’ll come across some moment in Dante’s voyage which will resonate with you. This needn’t be a matter of faith, it could be related to your health (physical or mental), or deciding what you want the next step of your own life’s voyage to be. Even in matters exterior to yourself its easy to find parallels between our world and Dante’s. I found myself thinking of modern political discourse and social unrest at multiple times when I read the Divine Comedy and found that Dante’s approach to the issue revealed some of my own thoughts on the matter, despite Dante having lived 700 years before me and that he was writing about a political world so far removed from me physically and temporally that at first glance it would seem hard to draw connections. I think that is the beauty of the Divine Comedy that is easy to miss from the title alone. While the poem is a comedy (in the classical sense) of Dante’s voyage to God, it is also – and more importantly – a humanistic tale of perseverance; a message that “this too, shall pass.”

That’s why I feel like it’s important to read the entire poem (with commentary). Per the research I’ve done and according to the Hollanders, most readers of Dante never progress past Inferno. It is, after all, the most famous portion of the poem and would almost certainly win in a contest of popularity. It’s definitely my favorite of the three parts. Yet, while Inferno can stand on its own and holds the title of my favorite part, to just read Inferno would kind of be like only reading The Fellowship of the Ring and eschewing The Two Towers and Return of the King. If you only read Inferno you’ll missing some of the most important aspects of Dante’s voyage. Sure, Inferno probably captures our imagination the most, after all, Hell is interesting to think about – but Purgatorio and Paradiso are critical pieces in the overall message of Dante’s poem. Without them, a lot of themes I’ve discussed in this post are lost. Now, that said, I fully admit that Paradiso can be a struggle. I would rate Inferno a solid 5/5 Stars with a 6th Star being appropriate should such a thing exist. Purgatorio I’d rate at a 4.5, though if I were forced into a whole number system it would eek its way up to a 5 over a 4. Paradiso, however, I would have initially rated as a mere 3. That said, by the end it had worked its way up to a 4, but I’m confident that the 4 is the highest score I’d ever give Paradiso independently (though the Divine Comedy as a whole sits at a solid 5 Stars for me (mathematical averages be damned – or, as Dante might put it: let the circle be squared). Most of this stems from the inherent difficulty in Paradiso that Dante opens the poem with and reminds us of at repeated intervals: how can a man, a flawed mortal man describe Heaven, let alone God? It is in this sense, an “impossible” poem. It’s much easier for a man such as Dante to describe Hell and Purgatory (even if placing specific people in these places has repercussions), but to describe Paradise itself and GOD? Well, that’s frankly borderline heretical. But Dante did, and in doing so he had to hedge his bets and rely on complex similes, metaphors, and philosophical rhetoric. The end result is that portions of Paradiso left me feeling so bored and drained that I seriously considered giving up on the poem, this in spite of how much I had enjoyed Inferno and Purgatorio. However, with the commentary (itself bordering on too complex at times) to guide me, I worked my way through Paradiso and I have to say that Paradiso is itself a lesson in “upward motion” because it gets far, far better as it goes on.

So, while I would say you really need to read the whole poem (as Dante intended) I am also willing to say that there are portions in the poem that are just downright challenging; namely the end of Purgatorio and sporadic cantos in Paradiso – but that the end result is worth the mental effort required to follow along with Dante. I might be less willing to request you make such an effort had the poem not moved me a great deal personally. Now, here I may have to disappoint you, as even though this blog is intended as a message to my future self, the specific aspects of the Divine Comedy that moved me to tears (yes, not an exaggeration), laughter, and at time palpable anger are things which I don’t wish to share publicly. They are, in a a way, between Dante and I. Still, as an example by proxy I can share the story of someone else who just so happened to be fundamentally moved by a line which also deeply resonated with me.

It is difficult to share this specifically without spoiling at least one aspect of Inferno but in truth to read the line independently of your own experience (that is, your own voyage with Dante) doesn’t lend it the power that I (and others) felt when they read it. It many ways, to excise a single line from the Divine Comedy is much akin to only reading one portion of it (i.e. Inferno) – or to read one line of the Bible and think you’ve figured out Christianity – you miss the power of the message as a whole. Still, I was so moved by this particular part of Inferno that, in learning more about it, I stumbled across someone else’s story, which I’ll briefly recount here with links to the articles I referenced. Be forewarned, much like the comedy itself the following story starts tragic, but ends with a message of hope.

The line in question is:

“Then we came forth, to see again the stars.”

Like I said, not much by itself, it’s more about what it represents in the moment. That representation struck a chord with Jayson Greene. In 2015 Jayson and his wife Stacy were dealt a crushing blow from the universe when, in a freak one-in-a-million accident that is so unlikely that for most parents it only ever lurks in the corners of their nightmares, their 2 year old daughter Greta was killed by a falling brick. I won’t recount Greene’s entire story here, but this Time Magazine article does cover it in discussing the book Greene ultimately wrote about the ordeal and its aftermath. This New York Times article does the same thing, better, but might be behind a pay-wall for you. If you can read the NYT I’d recommend it over the Time one, if only because it has more depth. The reason I bring this incredibly sad story up is because of the impact that the Divine Comedy, specifically Inferno, and specifically that line above had on Greene. In starting the healing process of losing a child due to tragic chance, Greene and his wife remembered that one part of Dante’s voyage, and through it found the hope to persevere, survive, and to hope. Greene, an already established writer, would eventually write a book about this chapter of their life called “Once More We Saw Stars” which echoes directly Dante’s message from over 700 years prior. In an interview with the Atlantic (which I highly recommend reading to understand the power of Dante’s voyage to help heal), Greene talks about how Dante’s journey shaped his perception in the aftermath of the tragedy and how its message became a “talisman” that he carried around with him as his family tried to heal while also remembering the child they had lost. If you’re interested in the book, here is a NPR review of it, and it’s widely available.

While I do not know Greene, nor have I contacted him, nor do I claim to have experienced anything similar to loosing a child in such a (let alone any) situation, there is a shared bond over Dante’s work, over his own voyage, that can be found. The portion of Inferno that moved me also helped two parents to heal. Though I haven’t recounted my specific experiences on this post, Greene’s story serves as just one voice (among the countless multitudes of them) highlighting the timeless message of Dante’s Divine Comedy.

And so, with that, I’ll close out this lengthy endorsement of the Divine Comedy and its message of hope and perseverance by sharing a thought from Dante about why you must always carry on in your voyage, and how that voyage is yours alone:

“If the present world go astray, the cause is in you, in you it is to be sought.“

–Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy