Life is Strange

Well, yes, it is. But this post isn’t about my life, it’s about the video game Life is Strange. It’s also the very first post in a brand new category on Dinosaur Bear, which is unsurprisingly called “Video Games.” I’ve thought about writing about video games off and on over the course of this blog, but I’ve finally decided to start doing it. So consider this the inaugural post. If you have no interest in video games, then you can simply ignore all future video game related postings and stop reading now. 🙂 That said, my goal isn’t going to be to review these games in a traditional sense where I go through a line-item analysis with a point total at the end – as thousands of review sites already exist, and are much better funded. Instead I’m going to focus on why I think the game is important, not just as a video game, but as a piece of art – which video games are, sorry if you disagree. So I won’t get bogged down in (too many) nerdisms here (that’s a lie), but instead I’ll try to explain why the game mattered, to me.

Now, with that out of the way:

_____________________________________________

Dinosaur Bear Video Game Series Presents:

Life is Strange

Warning – Extreme Spoilers Follow

Life is Strange is an episodic video game from Dontnod Entertainment (developer) and Square Enix (producer) which was released between January and October 2015. I didn’t get around to playing it until February 2016 after I purchased the “complete” game for PC on sale during Steam’s holiday sale. An episodic game is exactly what it sounds like, it’s a game which is released in episodes – kind of like a TV series. Of course (depending on the game) these episodes tend to be longer than a TV episode, in the case of Life is Strange each episode ranges from 2 hours on the low end, to 5 hours on the high end. Since I tend to be someone who explores almost everything in a video game, commonly referred to a as a “completionist,” I trended towards the higher end of game play time from each episode. In total there were 5 episodes, which were entitled “Chrysalis,” “Out of Time,” “Chaos Theory,” “Dark Room,” and “Polarized,” sequentially. The game is notable because it is extremely choice-driven, sort of like those “Choose your Adventure” books, except this time it’s more like real life in that you often only make things worse despite trying to fix them.

Life is Strange isn’t really noteworthy on the graphical front, in fact the graphics are pretty dated looking for a game released in 2015. However, they are stylized, in that the game doesn’t really seem like a graphical failure, but rather it seems like it achieved its vision, even if that vision wasn’t pushing any graphical boundaries. Additionally, the control scheme is extraordinarily basic, there is absolutely nothing about the controls for this game that should win any awards. In fact, there were times where I was trying to move around in a small environments where I felt like the controls were a bit clunky.

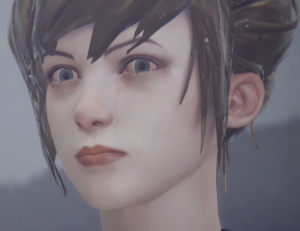

Technical details aside, what makes Life is Strange one of the most notable games I’ve ever played? Well, it’s a multitude of factors rather than any one specific thing. For starters, you play as an 18 year old girl by the name of Maxine Caulfield, though I’m pretty sure that 99.9% of the time she is referenced as Max.

The Basic Plot and the Protoganist

The protagonist is actually one of the major factors that made this game interesting for me, since I am most certainly not an 18 year old girl dealing with 18 year girl old problems in 2013 (the year the game was set in). But before I can explain why this ultimately became a strength for the game, I have to explain a little bit about the game’s setting.

Life is Strange takes place over the course of the week of October 7th, 2013. The game is set in the fictional town of Arcadia Bay, Oregon, which seems to be a blend of Twin Peaks and a trove of Pacific Northwestern tropes and idioms. In fact, I think that there are probably elements of this game that could only be appreciated if you grew up in the Pacific Northwest. That said, the entirety of Arcadia Bay is typical of small town America. There is very little to do, the town’s economy is mostly shot, there are a small cluster of families who control most of the wealth and power, and most of the youth dream of getting out to Portland, Seattle, or California. So on that note, the theme of disenfranchised youth in a small town going nowhere fast is a universal theme, and one that I can personally relate to.

However, what makes Arcadia Bay different than any-town America is Blackwell Academy.

Blackwell Academy is an interesting institution – of a type I’d never heard of before. It’s a Private Senior High School. So, literally only high school seniors go there, so it’s effectually an entire school devoted to one single grade. Further, it’s a live-in school, so that students have dorms on campus. Maybe this is a thing, I mean I know a lot of private schools are live-in, but I’d never heard of a single-year school before. Anyways, despite its humble location, Blackwell is a nationally recognized Senior High School noted for its Arts (particularly photography) and Science programs, and is known as a “feeder” school for the Ivy Leagues. If you were wondering why some random town has such an academy, it’s no great surprise that its history is directly tied to that cluster of wealthy families I mentioned.

And it is Blackwell Academy where the story of Life is Strange begins and ultimately ends. Max actually grew up in Arcadia Bay, but her family left for Seattle when she was 13. She left behind her bonafide childhood friend Chloe Price, whose father had recently been killed in a car accident (talk about shitty luck for a 13 year old – losing Dad and BFF back-to-back). 5 years later Max returns to Arcadia Bay to attend Blackwell, which was possible due to a scholarship she received. Max is an aspiring photographer, which is a central element to the game. Interestingly enough, she is completely obsessed with analog film, rather than digital – which despite the game’s painfully hipster overtones actually ends up adding to the story in a fairly critical way. She had had essentially no contact with anyone in Arcadia Bay during her 5 year absence, including Chloe.

So you’ve got the basic gist of the core story. The main character is an 18 year old named Max, she is at Blackwell Academy, she wants to be a photographer, and she hasn’t had any real contact with her childhood BFF Chloe in over 5 years. From there we’ll start adding in ancillary characters, but that is the basic construction, and it’s pretty much where the game begins.

And coincidentally it’s also where it gets strange.

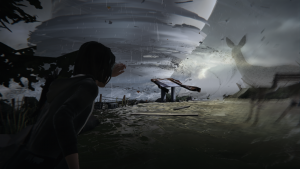

The game starts with Max stuck in a massive-ass storm, watching helplessly as a gargantuan cyclone blazes towards Arcadia Bay.

And then, despite your best efforts to not get swept away, Max gets crushed by a falling lighthouse. Yep. Game Over?

Not so much. After this rather climatic intro, Max wakes up in the middle of her photography class.

And here the game becomes incredibly mundane. The developers did an incredible job of making Blackwell Academy feel like high school. Sure, there is an element of elitism in the air that a public high school may not have, but your basic clique and personality types are the same. Even the teachers themselves blend into the atmosphere in a way that is completely believable. Most of them are non-exceptional in an honestly invigorating kind of way not seen in most video games. There are two “sort-of” exceptions to this, the first of which is Max’s photography instructor Mark Jefferson.

Mark Jefferson is a famous photographer turned academy instructor (and thus why he stands out – at least for now). Despite Jefferson being held in high regard, there are hints that he is a bit of a “has-been” in that most of his really famous work was done over a decade prior to the start of the game, and now he is a teacher at a small town (albeit prestigious) academy for high school students. That said, Max has a bit of a professional obsession with him (but not physical, that goes to “Rich Bitch” and seemingly-antagonist Victoria Chase), and he played a big part in her applying to Blackwell. I’ll get to the other “sort-of” exception person in a bit.

The game, which you’ll have to remember started with a scene of climatological apocalypse, quickly becomes about the high school drama of a teenage girl, who isn’t really unpopular, but certainly isn’t in the “rich and/or cool kids” club (which is literally a club at Blackwell, called the “Vortex Club” – the irony with the cyclone is not lost). Heck, once you get out of the classroom, which itself involves lots of little high school tropes, the official “intro” scene involves listening to your MP3 player while wandering the halls, which sort of introduces you to the cast of extras and secondary characters.

It’s also when the game’s amazingly well selected soundtrack starts up for the first time, featuring “To all of you” by Syd Matters as you wander around.

While I was enjoying the music, at this point I was starting to wonder just how “into” this game I was going to get. While I generally like games that stray from the rails, I wasn’t overly thrilled about paying $12.49 for a “teenage girl simulator” – complete with comments about being on your period when examining a tampon dispenser. However, that feeling didn’t last long. For one, even if it would have remained as a “teenage girl simulator” the character development was pretty incredible. Second, it didn’t stick to that theme for long. While Life is Strange is choice-driven with lots of branches, the environments themselves are fairly linear. For instance when you are first given free reign to explore Blackwell, you can explore and interact with a lot of things and people, but ultimately you have to enter the girl’s restroom for the story to actually progress.

Once you do finally make your way to the restroom and wash your face (again, mundane stuff here), a blue butterfly flies into the window and lands on a bucket.

That’s pretty much when things begin to go from “Sims” to “What the Hell.”

After Max takes a photo of the butterfly, a guy by the name of Nathan Prescott barges in (yes, into the girl’s restroom).

If it wasn’t obvious from his name, Nathan is one of the “Rich Kids” and not only that, his family is the richest (and nastiest) in the town, so Nathan is on a bit of a pedestal, he also appears to be a bit of a psychopath as he is ranting and raving to himself in the bathroom, which is the first time you see him.

A few moments after Nathan enters and starts screaming to himself, another girl enters who Max (hiding behind a stall) doesn’t recognize. After a confrontation in which its revealed that Nathan had been dealing/buying drugs, Nathan goes berserk and pulls a gun on the other girl, and ends up shooting her semi-accidentally.

In the last moment, Max dives out from her hiding spot and tries to stop whats happening, and stop it she does. She also stops everything else. More specifically, she not only stops everything else, time starts moving backwards.

The player (and Max) then see the bathroom homicide reverse itself, slowly at first, then faster, and faster until the screen blurs out and you “wake up” again back in the classroom where you started after waking up from the cyclone dream.

In my opinion, this is kind of where Life is Strange actually begins.

After waking up, Max begins to figure out that she has spontaneously generated the ability to reverse time. After testing it out by making sure the same things happen, and manipulating a few of Mr. Jefferson’s questions, Max rushes off to save the girl from the restroom (where she encounters the blue butterfly once again), which she does by pulling the fire alarm, sending Nathan fleeing before the fatal gunshot.

In a single event, this has gone from a weird teenage girl simulator with the odd nightmare about weather, to a full-bore science-fiction game where there are all sorts of questions and very little answers. And it’s here that the game starts to become fairly divisive. It’s also where I’m going to stop sequentially running through the game, because that would result in an extremely long post for me, which is saying something. The discussion of the introductory portion of the game is really the most crucial building block in understanding why I think that Life is Strange, while far from perfect, is a damn good game that even non-video game players could enjoy.

What Life is Strange does amazingly well, is that it continues to feed the player a mundane world, despite exceptional events unfolding in it. It’s not like Max instantly becomes a superhero when she finds out she can reverse time. It’s quite the contrary actually, as the time control bit is secondary to being (or rather, trying to be) an ordinary teenage girl with ordinary teenage girl problems. Max still has normal friends, and normal high school enemies, and the town is still normal. In fact, other than Max and two other things, nothing in the entire game is paranormal, or super-human. Sure, some real problems arise, but these are all grounded firmly in reality. The game almost makes you expect that Max is going to meet another person with this power, but she doesn’t. At no point does a super villain arise who can fast forward time, etc. The demons of Arcadia Bay are wholly and entirely human, and even more interestingly, the two other “paranormal” events are directly caused by Max, rather than independently existing.

In this regard, I found the world to be incredibly believable, and the characters within that world to be even more realistic. As a result, I found myself relating to them even more than I might otherwise have if it had turned into a sort of X-Men universe where Max was just one of many, and her ability came down to some mutation. Nope, none of that here. In truth, there really isn’t a whole lot of information given to the player (and Max) about her newfound abilities and a good deal of the game is spent trying to figure out just what in the hell is going on, while simultaneously living a normal small town life.

The Deuteragonist

Eventually Max is reunited with her childhood friend…

…Chloe Price, who predictably was the girl in the restroom.

Chloe, by her own words, becomes Max’s “side kick and chauffeur” and is actually – if I remember correctly – the only person who Max is forced to tell about her newfound ability, which brings about a series of pretty damn funny “proof of concept” moments that anyone who has ever been an American teenager (male, female, or otherwise) could relate to.

But not all is well in Chloe’s world. Since the death of her father and Max’s departure 5 years prior, life hasn’t been anymore kind to Chloe. Her mother, Joyce, remarried a man named David Madsen (who is war veteran with paranoia and PTSD who got kicked off the police force and is now a security guard at Blackwell) whom Chloe seemingly hates, and more importantly, the friend she made in Max’s absence – Rachel Amber – has gone missing under extremely mysterious circumstances.

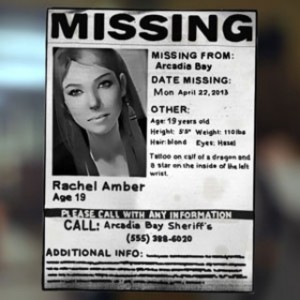

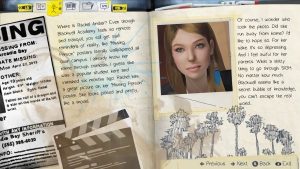

Rachel’s disappearance isn’t actually news to Max as “Missing” fliers for Rachel are encountered within the first few moments of the game and becoming increasingly prevalent as the game goes on (Chloe was placing most of them as the official search had since been called off).

So Chloe comes with her own baggage, which when coupled with Max’s simultaneous guilt over leaving Chloe and jealousy towards her “new” best friend, makes for an anything-but-placid backdrop to the “BFFs” foreground.

So, the protagonist and deuteragonist approach everything unfolding in Arcadia Bay with their own respective lenses, and seeing these two separate, highly-developed, characters deal with the ramifications of time travel becomes increasingly engrossing as the plot unfolds.

Max’s Powers

Also unfolding with the plot is Max’s power.

Max essentially has four powers by the end of the game:

- “Rewinding” time

- Stopping Time

- Precognition

- Time Hopping (also called “Focus,” which occurs via photographs)

At the start of the game you are limited to precognition (e.g. that huge storm “dream”) and rewinding, and you can only go so far back before you get severe head pains and your nose starts bleeding.

Eventually though Max becomes more in-tune with her power, and even gains the ability to stop time entirely – though this seems to be even more physically damaging for Max and seems highly circumstantial, as it can’t be employed at will.

The pinnacle of her power (insofar as we know) later comes via photographs. Max can hold a photograph – though seemingly it needs to be a physical print (thus the analog connection) – and travel back in time to the moment that photograph was taken.

This results in a HUGE time clusterfuck (paradox style), as Max is not only changing the recent past, she can now alter entire lives by returning to pivotal points, such as to her 13 year old self in the moments before Chloe’s dad walked out the door to pick up her mom and was killed in a car wreck. Max (and the player) are then given long reaching decisions such as whether or not to save William (Chloe’s dad). Of course the photo-time-travel power has its caveats. First, Max is limited to the immediate area where the photo was taken, this might be as small as a 20×20′ space. Second, she has to be in the photo, for instance she can’t “inhabit” other people’s histories, only her own. Third, the Butterfly Effect – which creates all sorts of problems for Max, and often your attempts to make things better, often end up making things much worse. For instance, in her attempts to “save” William Max ultimately ends up getting Chloe killed, and not only that – Max is the one that kills her (though to be fair it was a mercy killing – removing her from life support – as Chloe was slowly and painfully dying from her own car wreck in that timeline).

Further, each time Max uses her powers – be they rewinding, stopping time, or time traveling – things begin to get more and more “uncoiled” as these timelines begin to clash and riding alongside the Butterfly Effect is the Chaos Theory, and the fact that Max seems to be slowly killing herself with her powers.

[Side note: If you are interested in learning more about the Butterfly Effect in a more “streamlined” and narrative way, do NOT go watch the 2004 film by the same name, instead do yourself a favor and read “A Sound of Thunder,” which is a short-story and literary classic by Ray Bradbury.]

The way these three powers manifest themselves in terms of gameplay is fairly straightforward. You hold down a button to reverse time, you do the same to stop time (again it’s contextual), and you use the analog sticks to “focus” on a picture in order to travel inside of it. Most of the time you have pretty much free reign over the reversal power, meaning that you can be very manipulative (think Groundhog Day) in both good and bad ways. As the story progresses, Max is met with a barrage of choices, and while you can reverse and change your choice or action in the moment, if it gets too far in the past then its gone forever (lacking a photo).

As a result, there are essentially three “Tiers” of decision arcs in the game.

The first tier are those decisions that I’ve labeled “Inconsequential” which isn’t entirely accurate, but they ultimately don’t change the flow of the game or how other characters perceive you in the long run. For instance, you might ask someone what they did last night, and then instead decide you’d rather ask them what their plans are for tonight. Neither answer is especially important, and you build rapport either way, kind of like real life.

The second tier are those decisions I’ve labeled “Consequential.” These decisions are those that have a noticeable effect on Max and her world. A good example is whether or not you save the “Rich Bitch” (Victoria) from having paint dumped all over her. While paint vs. no paint doesn’t result in anything major happening, it does serve as an impetus for how your relationship with Victoria pans out.

The third tier are those decisions I’ve labeled “Majorly Consequential.” These decisions, as made obvious by my title, have HUGE implications. As in, people will live or die based on your actions. Though they aren’t always that severe, they do have massive impacts on the story and can literally change the flow of the rest of the entire game. And here is where I find a rare fault with Life is Strange. It’s not that I don’t like being forced to make a “Majorly Consequential” choice, it’s that the game holds your hand a bit too much when it’s happening. For example, at one point Max has to decide whether or not to (try) to shoot a drug dealer named Frank (though his character is actually much deeper than initially meets the eye) who is threatening Chloe with a knife.

When that happens, this is what happens in the game:

Time freezes, things go all red and wobbly (similar to standard time reversal, but more severe) and then you are left with anywhere from 2 – 4 decisions to make. What I don’t like is how obvious the game makes it that this is a huge decision. It should be contextually obvious just how big of a deal something is – and the thing is, Life is Strange does a great job of contrasting the “little” moments with the “big” ones, so that these “Red Screens” seem like a bit too much of a hand-holding bit for my taste. Then, to make it even more simplistic, once you’ve made your choice, an on screen prompt comes up and says “This action will have consequences…” as if the huge time freeze wasn’t enough. I’d have much preferred that they left these “Major Consequence” moments in their “natural” state, so that 1. They happened in real time, and 2. It was left to the player to determine whether or not to rewind and change things. As is, Life is Strange holds up a massive WARNING sign, which it doesn’t do for 1st and 2nd tier decisions. Canonically, it also doesn’t make sense for time to freeze in these moments, as Max isn’t actively engaging her powers. That said, I still really like how consequential (and even inconsequential) most decisions are, and despite my mechanical issues with 3rd tier decisions, I really think the system adds to the overall plot.

Sectional Plot Analysis

As for the plot itself, it’s actually really good – but not in any grandiose way – what makes it great is the sum of all its parts. For the purposes of that analysis, I’m going to break my coverage down into three areas: Antagonist, Supporting Cast, Setting. Obviously the two main characters are important, but I’ve described them pretty heavily above.

Also, while I don’t really cover the soundtrack for Life is Strange – it’s absolutely amazing, and in many ways is equally important to the narrative plot. The soundtrack features a variety of songs such as the aforementioned “To All of You,” as well as others such as “Obstacles,” “Crosses,” “Something Good,” “In My Mind,” “Mt. Washington,” “Got Well Soon,” and the haunting finale, “Spanish Sahara.” While listening to them independently of their in-game scenes doesn’t yield the same results, I would recommend listening to those selected tracks to at least get a vibe for the ambience of game (there are some other tracks, but these are the ones that stick out to me the most). With that said:

The Antagonist

Nope, it’s not Nathan Prescott. It’s Mark Jefferson.

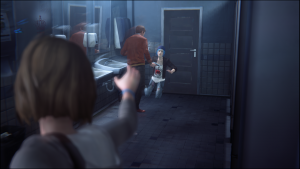

Yep, seen here after literally shooting Chloe in the head (in that timeline), Mark Jefferson is the criminal mastermind and generally fucked up snuff fetishist who has been responsible for a long line of missing persons and kidnappings. If you guessed that he is responsible for Rachel Amber, then you would be correct, though Nathan was involved in that one – but I’ll explain Nathan in a moment. See, Jefferson is obsessed with the moment a person loses their innocence. This doesn’t actually seem to be a sexual thing, as none of the victims are sexually abused (at least this isn’t implied or shown), but instead he wants to capture – on film, of course – the exact moment where a victim loses their “well-being” for lack of a better word. To put it more simply, he likes taking photos of people who have just realized they are going to die.

But Jefferson doesn’t always kill his victims, though how many actually live is left ambiguous. Instead, there are some, like Kate Marsh, who aren’t killed, but go on to deal with pretty shitty consequences anyways, but more on Kate in a moment.

What makes Jefferson so good is how unexpected he is. Like the old adage that serial killers hide in plain sight (they often do), Jefferson slips by detective-team-in-self-training Max and Chloe time and time again. I’m generally fairly good at figuring out mysteries, I don’t know why, but give me evidence and I tend to be pretty accurate at putting together the pieces. Not the case with Life is Strange. In fact, at the end of Episode 4 – when Jefferson comes out of the shadows and kills Chloe (and subsequently is revealed as being involved with Rachel’s death) – I was pretty much blown away. To be fair it’s literally in like the last 30 seconds of the episode, and Max gets stuck with a needle (containing a powerful tranquilizer) from behind so her powers fail her at a critical moment and then Chloe gets her brains blown out right in front of you, then the episode ends. All that happens in maybe 20-30 seconds.

Now fortunately for me I wasn’t playing these episodes as they came out, so rather than having to wait for two months I only had to wait until the following weekend to play. Long story made short, Max gets Chloe back, via her expanded time travel abilities – but it isn’t an easy process by any stretch of the imagination, and Max seems to fuck up the flow of time even more by bringing Chloe back from the dead yet again.

Now as for Max’s powers and how they relate to Jefferson, it’s done really well. Jefferson has no “Ah-hah!” moment, nor does he ever even realize Max has powers. Jefferson is the predator. He is arguably more intelligent – and certainly more devious than Max, and he is physically stronger. As a result, Max’s only real trump card is her powers and to a lesser extent her relentlessly inquisitive nature. So during the “show-down” with Jefferson, the events can play out in a huge number of ways.

I won’t recount them all, but results can range from Max dying, to Victoria Chase dying, to David Madsen dying, to Nathan Prescott dying (or already being dead by the time the showdown happens), and of course to Jefferson himself dying. While it’s pretty obvious that Max would want most of these parties to survive, the Jefferson decision is ultimately left up to the player. Do you spare him, and let the justice system deal with him (via a massive amount of evidence both Max/Chloe and David Madsen have dug up)? Or do you create a situation in which he is beat unconscious and then shot by David? It’s entirely up to the player – depending on how you and Max have grown.

For what it’s worth, I saved Jefferson simply because I ended up really liking David Madsen, despite the game’s attempts to make you not like him due to how he treats Chloe (and others – with the exception of Joyce, who he treats very well), I guess I tended to give him a lot of leeway given his PTSD, and I didn’t want him to deal with having killed Jefferson from a legal perspective. Interestingly enough, since you can control time, you can chose to both spare and kill Jefferson, though ultimately you have to move forward in one of the timelines – you can’t have it both ways.

Still, whatever the outcome, Jefferson is a great antagonist precisely because you have no idea he is the antagonist until it’s too late. Then, even with her powers Jefferson puts up one hell of a fight – both mentally and physically – before ultimately being subdued and/or killed.

The moment where Jefferson is revealed as the “killer” is by far one of the best moments I’ve ever had while playing video games.

The Supporting Cast – Five Selected Characters

Life is Strange’s supporting case is too large, varied, and detailed to fully recount here. You’d really need to play the entire game or spend like 10 hours reading the Life is Strange Wiki. Instead, I’m going to focus on a few characters who really stood out to me.

1 – Nathan Prescott

Nathan is a very interesting character, not only for strictly narrative purposes, but also for the statement he makes about modern America (which is a theme running across many characters). While Mark Jefferson is the insidious mastermind, Nathan is the game’s “target” from the first scene in which he shoots (at least temporarily) Chloe. Pretty much everything in the game is designed to make you loathe Nathan. That said, it didn’t quite work on me. While I fully admit that I was blindsided by Jefferson, I didn’t bite on Nathan as the true villain. Sure, Nathan is a bad actor, but he is not the bad actor.

For starters, Nathan goes against the mold in that he isn’t just the traditional “Rich kid who is actually insecure and deep down is a good person” (that honor goes to Victoria), instead Nathan is the “Rich kid is actually severely mentally ill and whose family is trying to cover it up.” Nathan is wholly unstable and is also addicted to a wide variety of drugs (many of which are provided by Frank). As the story progresses it becomes more and more obvious that his dad (the richest and most powerful man in Arcadia Bay) pretty much disdains him, and that his family is more concerned with hiding his (Nathan’s) mental illness than they are trying to help him. The result is that Nathan is openly shamed for being mentally ill, vilified for it, and despite having ample financial resources, is quite alone.

I think I picked up on this undercurrent earlier in the game than most people, as public sentiment towards Nathan was pretty abysmal in the earlier episodes. It doesn’t help that he is dangerously violent and erratic and that he overtly threatens and generally causes shit for the characters the game wants you to care much more about (though admittedly this was still probably a “failing” on my end, as it was pretty obvious that Nathan was not well by that point – but there’s only so much you can do with a gun in your face). Sadly, in the initial timeline things do not end well for Nathan. For one, he gets the ever loving shit beat out of him by friendly neighborhood nerd and potential love interest of Max, Warren Graham.

Despite my reservations towards Nathan, I still allowed him to get the shit knocked out of him mainly because I was tired of him pulling guns on people (it happens more than once). And then, shortly after getting his shit kicked in, Jefferson hunts him down and kills him. Yep, happy days for the mentally ill kid. Jefferson wanted him dead because he “knew too much,” and was directly related to the disappearance and death of Rachel Amber.

As Max and Chloe eventually find out (after a long trail of clues which lead to Rachel’s buried body), Jefferson had been “using” Nathan Prescott as a way of funding his obsession. Nathan had come to view Jefferson as a father figure, and with his own mentally deranged views on the world and photography, Jefferson convinced him that he would be his mentor (when in actuality Jefferson was just using him to access his family’s fortune). The end result is that Nathan accidentally overdosed Rachel while trying to impress Jefferson, which killed her. This obviously infuriated Jefferson, and ultimately it was Nathan’s “screw up” that caused Jefferson’s scheme to unravel. So, when the shit starts hitting the fan, Jefferson kills Nathan too and frames him for everything that has happened, leaving only Max (who was then trapped in Jefferson’s Prescott-funded “Dark Room”) knowing the truth. Nathan’s last act is to leave a voice mail on Max’s phone where he essentially breaks down and reveals what has happened, all while verbally trembling in terror at the fact that Jefferson was actively seeking him out.

So Nathan, despite being very unlikable, is actually a victim himself, and not only that – he is also grappling with a severe mental illness. Though he is never explicitly diagnosed, a lot of people had deduced that he was a paranoid schizophrenic and obsessed with death based on some files you can access at one point during the game when you break into Blackwell.

Unfortunately for Nathan, just like many people with mental illnesses, there was no help.

2 – David Madsen

If you were to look up the definition of “Washed up” David Madsen could fit comfortably right next to it. At first David seems to have no qualities that I’d normally find redeeming. He is portrayed as a potentially violent asshole who is extremely invasive and aggressive and seems to be stuck in his glory days of the military. However, like many characters in Life is Strange, David has a much deeper story. For starters, he was in the military and was a combat veteran. Not only that, he apparently saw some really bad combat. The game never reveals just which conflict (fictional or real) that he was in, but that actually doesn’t matter. What matters is that after it was over, he was honorably discharged and essentially left on the streets without an ounce of post-war counseling. He then became a cop, but at some point his paranoia and PTSD started to overtake his life and he was kicked out of the police force for being mentally unstable. At some point during this time he met Joyce (Chloe’s widowed mom) at the diner she works at and eventually they were married, and unlike many other things in David’s life, the marriage seems to be mostly happy.

So, removed from the military and kicked out of the police force, David becomes “Head of Security” at Blackwell and proceeds to become immediately hated by just about everyone, students, staff, and faculty alike. That said, he did (by others’ own admissions) make the campus a much safer and secure place – though at expense of some civil liberties.

Anyways, throughout most of the game you deal with David as a security guard, Chloe’s Stepdad (whom she lovingly calls everything from Step-führer, Step-shit, Step-ass, Step-douche, Step-dildo, Step-troll, Step-prick, to Step-crack), and eventually a critically important ally.

The plot allows Max multiple chances to forge an alliance with, or make enemies with David, but I found myself siding with him over and over, though I wasn’t entirely sure why. For whatever reason he always struck me as someone who really wanted to help, but was just completely out of place in the world. There are brief moments, such as when he is working on a car in his garage (David is apparently a skilled mechanic) where you see a more fragile side of him, which, despite being at about a 1:100 ratio with his asshole side, was enough to convince me he was a good friend to have. The downside is that siding with David makes pretty much everyone else (except Joyce) pissed at Max, but I dealt with that. The thing is, towards the end of the game, an alliance with David proves extremely valuable as he is your best bet at defeating Jefferson.

David seems to be a parable about the “Vietnam Vet” in that his backstory reveals that he game from a loving, albeit poor home, was whisked off to war – was severely fucked up in the process – and then dumped by both the government and society. What I think is really cool is that if Max chooses to swim against the current, she can not only “befriend” David, but also improve his relationship with almost everyone else. The unfortunate reality is that none of David’s endings are especially happy.

But you can choose to make them a little better, and sometimes that’s all a person can do.

3. Kate Marsh

Kate Marsh is a notable character in that, for most players, she represents the first of many “Oh my God what I have done” moments in Life is Strange.

At first Kate is little more than the token “Religious Girl,” and she sort of represents the recent trope of religious people being easy to pick on. Despite not really being religious myself, this has always been something that really irritates me – and Kate sort of points out a lot of the hypocrisy in picking on all religious people for being intolerant. However, Kate becomes much less about being the “Religious Girl,” when she reveals that she was drugged at a Vortex Club party. While drugged she made out with a lot of people, which was of course uploaded to YouTube and subsequently led to mass shaming – from people who do the same thing on a weekly basis – and a constant bullying campaign against her. However, there is more to the story than a date-rape situation, as Kate wasn’t actually sexually assaulted, instead she vaguely remembers bright lights, a needle in her neck, and a “hospital room,” etc. Sound familiar? Yep, it should. Kate was drugged by Nathan, and then “made into art” by Jefferson. Fortunately for Kate she was one of Jefferson’s (few?) survivors, but unfortunately for Kate her life pretty much became hell afterward as her more radically religious family members all but disowned her. This leads to a long series of situations in which Kate is mercilessly bullied, and Max can either choose to help, antagonize, or do nothing.

As in real life, the decision to stand up for the victim sounds easy on paper, but in actuality, it brings with it is own swarm of problems. That said, in all but one occasion I stood up for Kate (and that situation was actually a red herring anyways) and dealt with the proverbial shit-storm of drama in the aftermath. However, despite Max’s best efforts, Kate continues to get worse and worse, and while Jefferson (still cloaked in innocence) seems like he is trying to help, he is actually manipulating Kate in plain sight (remembering that she had no idea Jefferson was involved), because he likes to play God.

As things get worse and worse, so too does Kate’s mental health, and eventually she jumps off the roof of Blackwell’s girl’s dormitory, killing herself.

However, Max can save her – maybe. This is the pivotal point in the game where Max both unlocks her ability to stop time, and the player also realizes that “Ok, yeah, so all those decisions actually matter.”

Max enters the area just in time to see Kate plummet to the earth (in front of a huge crowd of onlookers, some of whom are still making fun of her) and is able to stop time long enough to get to the roof (beating David Madsen who can be seen frozen in time trying to make his way up here [eventually it’s revealed that he erroneously left the door to the roof unlocked, furthering his mental strife]), however, once Max gets to the roof, she gets a major nose bleed and almost falls unconscious – e.g., no more powers. Sure this is stylistically convenient, but I didn’t mind it so much given that this was the first time Max ever stopped time.

The result is that you have to stop Kate from killing herself in real time with no powers.

Of course you don’t have to try to stop her, but let’s be real, it takes an ice-cold asshole to say antagonistic things to someone already on the ledge.

The thing that makes this scene incredibly powerful is because it doesn’t hold your hand. You don’t get any safety nets (pardon the pun) and you can’t rewind or pause to make decisions. If you want to save Kate, you have to think quickly, and you have to have seriously paid attention. If you were a good friend to Kate, it’s much easier because you know more. If you were a stranger in the crowd, then it’s far more difficult to talk her down. And, because Kate is already so fragile, it’s pretty damn easy to fail.

And if you do fail, that’s it, she’s dead. You can’t rewind, you can’t undo it – the world moves on. Unlike most video games and other media such as comic books, without Max’s powers, death = death in Life is Strange, and because Kate’s suicide event comes on so quickly and so fast, many players are forced to deal with that in a very blunt way. In fact, a lot of people hate this part of the game precisely because you are sort of thrown into it. I actually liked it, it made everything seem more visceral. Though dealing with the long to impacts of Kate dying fundamentally change the flow of the game.

However, the good news is that you can save Kate.

It just requires that you have really paid attention to her story, and/or have truly been a good friend to her. And I do mean really paid attention, down to myopic details such as her favorite Bible verses that she had circled in the Bible in her room. If you’ve cared about Kate, then generally Kate will care about you and step down from the ledge. And, when this happens, it genuinely feels good, and not only that, Kate ends up be extremely helpful in uncovering Arcadia Bay’s dark secrets, as you can even visit her in the hospital if you manage to save her.

The cool thing about Kate is that she is seemingly one of the few characters who things really turn around for (if she doesn’t kill herself that is). But what I really like about Kate Marsh isn’t so much related to the character, it’s what she “says” about suicide.

From the dialogue with Kate on the roof, it’s quite clear that she is killing herself as a way of “getting back” at her classmates and family, she also feels as though God has abandoned her. There is no glorification of this mentality though, the game makes it so that you are practically screaming at your screen how stupid this mentality is, yet at the same time screaming at Kate is one of the very worse things Max can do. Additionally, the finality of suicide, it’s extreme “solution” to a short-term problem is also highlighted. Kate’s actions unfortunately don’t really “change” anyone, they just make them feel guilty, temporarily. Even in her death, Kate doesn’t “get-back” at anybody, all she does is end her life and those who are most hurt are the ones who actually cared about her.

On the flip side, despite casting Max in the role of the savior, the game makes it clear that it isn’t really your (the player’s) duty to “save” Kate, it’s a choice. If you “fail” you haven’t really “failed” as you didn’t push Kate from the ledge. Despite the hugely heavy burden that Max (and you) will ultimately feel if Kate dies, at the end of the day it was never your fault. And while I was able to save Kate in my play through – mostly because I constantly talked to her about her pet rabbit (and later cared for it while she was in the hospital) – even when Kate lives the game highlights the “hollow” nature of lauding someone for “stopping” a suicide as if failing to do so was actually a failure on the part of third party. For a video game Life is Strange dealt with suicide in a manner that was far more sophisticated than I’ve seen in most media.

Interestingly, when Kate’s suicide (or not) first happened in Episode 2, so powerful was the player-base’s reactions to the scene that the developer later amended the end of the episode (live or die) to include a message about suicide and provided links and contact information for help lines and services.

4. Samuel Taylor

Ah yes, Samuel Taylor, Blackwell’s friendly and extremely odd groundskeeper/janitor. If his appearance alone isn’t enough to clue you in on his unusual persona, his voice certainly is. Of all the characters in Life is Strange, Samuel, or rather “Sammie,” has the most oddball and creepy voice. It’s like the developer rolled up all the stereotypes of a child molester that might reside in the mind of an upper-middle class suburbanite and then made Sammie out of the soup of ideas. From the first scene with him, where Max refers to him as being very “X-Files,” it’s obvious that Sammie is going to be quite a character in Life is Strange.

Except, really, he isn’t, and that’s what makes him great. Remember back towards the beginning of this post (yes, thousands of words ago) I mentioned that there were two real “sort-of” exceptions in Life is Strange? The first, as stated, is Mark Jefferson – and unless you’ve just been picking random sentences of this post to read you’ll know why. The second exception is none other than Sammie.

At the beginning of the game, Life is Strange tries to trick you into thinking that Sammie fulfills the trope of being the weird misunderstood person who is super nice and who the main character sees through the oddness and they bond (e.g. the “beast” trope). Nope, for one, more people like Sammie than Max initially seems to believe. While the “cool kids” all loathe him, outside of that sphere he is pretty well accepted, even with his weirdness. He doesn’t need to be “saved” by Max anymore than she needs to be “saved” by him. They are just two people who happen to be extremely weird on either the inside (Max, via her powers) or on the outside (Sammie, via his voice and general disposition).

Also, he doesn’t change anything, or even try to change anything. That is one of the core principals of the above “beast” trope – at some point the “beast” tries to become normal, things are ok for awhile, but then everything goes to shit. Nope, Sammie never tries to change, and if anything else, he is actually one of the more consistent characters as the week progresses and Arcadia Bay becomes increasingly fucked up in Max’s (literal) time storm. That isn’t to say that Life is Strange doesn’t try to make you think you’ve got Sammie figured out, in many ways he serves as the “Smart-Man’s” alternative to Nathan Prescott.

By that I mean that while Life is Strange purposefully catches the majority of people in the trap of believing that Nathan is the bad guy, it leaves just enough bread crumbs around to make the slightly more inquisitive believe that Sammie is the bad guy. It’s also as if the developers sort of imagined the player base falling into five major categories, based mostly on how “insightful” the individual player was.

Class 1: I have no idea who the killer is.

Class 2: Nathan is the killer.

Class 3: Sammie is the killer.

Class 4: A currently unrevealed person is the killer. [FYI this is where I was]

Class 5: Jefferson is the killer.

From what I’ve gathered, most people fall into classes 1-2 initially, and then a dedicated cohort fall into Class 3. Class 4 seems to be much smaller, and Class 5 is the smallest (though many people claim to have been in Class 5, because they have delicate egos and feel the need to lie about a video game).

The reason I call Sammie the “Smart-Man’s” villain is because he rides that line where “A little knowledge is dangerous” and the game tries to trick you into thinking Sammie is hiding something. What’s great about this is that Sammie isn’t hiding anything, ever, and is actually – from what I can tell – the only character in the entire game who doesn’t hide anything at any point. I guess in this regard, Sammie is probably the least realistic resident of Arcadia Bay, but at the same time, I felt like he blended wonderfully into the background of small town life, because it was the one weird person who was in fact, most real.

He also is one of the few people in the game that begins to realize that something very bad is happening in Arcadia Bay and doesn’t try to explain it away with science, etc. And most importantly, he loves animals, especially squirrels.

5. The Squirrels

Ok, so the squirrels aren’t really part of the supporting cast – at least not in the sense of the above characters, but at the same time they aren’t really part of the setting either. The squirrels serve a few purposes, in addition to just being squirrels, which are inherently cool. First, they are some of the earliest indicators that something isn’t quite right in Arcadia Bay (though it’s really the birds that get shafted first). Second, they allow for more humanistic interactions with other characters (e.g. Sammie). Third, they allow the player to change how Max interacts with the world around her. For instance, Max can ignore the squirrels entirely, or she can feed them and interact with them, and while these interactions don’t hugely effect anything, they do trickle into other aspects of Max’s life. Finally, they also serve a game mechanic function of allowing the player to seek out cool squirrel photos for achievements.

So, this 5th “character” is mostly here because of my implicit pro-squirrel bias, but that said, while other wildlife mostly serve as an indicator of Arcadia Bay’s health, the squirrels in Life is Strange provide an intriguing series of windows into not only Max, but the people who inhabit the world around her.

Also, they are squirrels, which is enough to merit a section in and of itself.

The Setting

So, now that we’ve devoted a fair amount of time to the characters, let’s talk about the setting. As mentioned, the entirety of Life is Strange (ok almost the entirety – there is one time line that puts you inside an art gallery in LA for a brief amount of time) takes place in and around Arcadia Bay, Oregon.

And while a lot of the plot unfolds at Blackwell Academy:

There are lots of sojourns into the town itself:

Chloe’s (or rather Joyce and David’s house):

An eerily quiet and very plot-centric junkyard:

And even some pristine Northwest coastal cliffs:

Of course this is just hitting some of the major areas, there also a myriad of other areas, ranging from an old farmstead (hiding a “Dark Room” beneath it), to sunny beach paths complete with the local drug dealer’s RV.

Overall, what makes Life is Strange’s setting so great isn’t the “macro” stuff – because honestly the game really doesn’t cover that much geographic space. Instead, it’s more about how much detail each area contains. For instance, when entering the Two Whales Diner for the first time, I spent a solid 25 minutes just going around and talking to people and inspecting things.

At its core, it’s just a diner. Nothing exceptional to see on its face. But instead, to the more keenly eyed player, you can notice the interplay between all the different stories in Arcadia Bay. For instance, some of the marker graffiti in the bathroom may (or may not) respond to things that have happened (or haven’t happened) in Arcadia Bay as the story unfolds. There are also even more nuanced elements, such as minor bits of conversations changing based on seemingly minor decisions you may have made days ago (in game time). Making it even more realistic, is that Max isn’t “invisible” she can’t simply go around poking into people’s stuff, people will react, and in the case of Frank, react violently. But still, as the town’s chief diner – and thus official grapevine spot – Two Whale’s has a lot more going on that meets the eye, and outside of a few instances, Life is Strange allows the player to miss a whole awful lot of it if they aren’t inquisitive and/or enough of a sleuth, and obviously this is just one location in the entire game, this level of details persists everywhere – from the physical locations, to small subvert details such as a ghostly doe, presumably Max’s spirit animal, which appears under select circumstances to Max alone and seems to be a more “GPS-like” element of her precognition (for instance, it leads her away from specific and imminent danger on more than one occasion).

So this gets back to my earlier point, Arcadia Bay is pretty mundane outside of the time storm and Max. I don’t mean mundane in a purely pejorative sense, I mean mundane in that they don’t “pop” out, they are normal, “simple,” and “expected.” At least on the surface. The truth, is that just like anyplace on Earth, there is the “Surface” and then there are the “Catacombs,” which hide all those skeletons (interestingly enough one of the instrumental songs from the soundtrack is entitled “Kids Will Be Skeletons“). Arcadia Bay might house a few more skeletons than normal, but it’s nothing unbelievable, e.g. there’s nothing ridiculous like Ancient Aliens or everyone-in-the-town-is-secretly-a-robot-happening-here. Instead, the setting is one where small-town boredom clashes with small-town greed, where the “lucky” are put on pedestals by the “unlucky,” and where times are getting hard – but only for those on bottom, and where as everyone goes about dealing with their problems, a psychopath moves among them. Aside the from the psychopath bit, which isn’t that outlandish (look at where most serial killers are from), Max is the actual oddity in Arcadia Bay, and through Max the player has to figure out what in the hell is happening, because it becomes increasingly clear that somehow, some way, Arcadia Bay’s imminent destruction might just be your fault.

So while I don’t overly praise the raw technical aspect of Life is Strange’s graphics, I do praise the attention to detail, the seamless flow between areas, the logical consistency of Arcadia Bay, and most importantly, how well grounded into their environment all the characters – and all their skeletons, stories, fears, longings, strengths, and weaknesses – ultimately are, and not only that, the pivotal role that Max can play (or refuse to play) in all their lives.

All in all, Life is Strange excels in creating an exemplary setting, not because Arcadia Bay is memorable by itself, but precisely because it isn’t.

The “Time Vortex”

If Mark Jefferson is the “human evil” in Life is Strange, then the “Time Vortex” represents a chaotically neutral element of destruction that seemingly can’t be stopped. Unlike Jefferson, who by the end of the game has fairly clear motives, the vortex seems to exist independently of the town’s skeletons and on many levels seems more linked to Max than to Arcadia Bay itself. The result is that Life is Strange presents two huge dilemmas within an extremely tight time frame. On one hand is the psychopath Jefferson, bent on carrying out his dark desires while hiding in a sheep’s clothing, and on the other side is a mysterious storm that seems to simultaneously exist and not-exist, but will (seemingly) assuredly destroy Arcadia Bay if it makes landfall.

This puts the player (and Max) into a precarious situation – even with Max’s time powers there is a pressing sense of urgency and you have to make real decisions about how to act. For example, do you go after the concrete problem of Jefferson – who will indeed be a real problem, or do you instead go after the abstract and uncertain storm which will completely wipe out the entire town – as opposed to Jefferson’s select victims. A classic case of “Now” vs. “Later” with a forced hand. Of course you can ultimately do both, though with dire consequences – Life is Strange gives no favors when it comes to softening the blow of the end-game decision arc.

The game intentionally makes the time vortex ambiguous, in fact it’s really left up to the player to determine what the hell is going on in the days leading up to the storm. Sure, the game begins with Max having a premonition of the storm, but that really doesn’t tell you much. Does the storm have something to do with Max’s powers? Yes, it does, but not in the way you might imagine.

So what kind of clues does Life is Strange offer up in regards to the storm while Max and Chloe are simultaneously trying to figure out who the kidnapper/killer is? There aren’t many of them, but those that exist begin to appear slowly and steadily, namely in the form of distressed and dead wildlife.

Birds are the first to go, popping up as small clusters of carcasses. At first there might be 2-3 of them, but they quickly surge to the point that entire lawns are covered in dead birds and garbage cans are stuffed full of them. Then, dead birds take on an even more ominous tone as the insects swarm them.

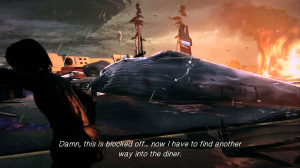

Notice the pattern? From there things get even more serious as entire pods of whales begin beaching themselves and dying.

But it’s not just the animals that begin to hint at a coming disaster, even the natural environment itself begins to change. Including freak snow storms.

Making this even more peculiar is the fact that the residents of Arcadia Bay seem to notice, or not-notice, these oddities in various capacities. Some people, such as Sammie, are just as in tune to the events as Max, if not more so, where other constituents such as the science teacher, Michelle Grant, seem almost oblivious and disbelieving towards some of the events – in other words, blinded by science (couldn’t resist myself). The result is that you don’t always know what is real vs. what is real to Max.

At some points the game seems to strongly suggest that Max sees the full truth of the pending storm, whereas others are just glimpsing it, but then at other times a character will display an insightful awareness of the situation (such as a homeless woman behind Two Whales) that makes you rethink your interpretation of all these signs.

Whatever the specific nuances that a player chooses to latch onto, the red flag rises time and time again, this storm is probably coming in some form, and you need to stop it, but we’re not going to tell you how, or even what “it” is. Subsequently, in more than one timeline, the storm does hit Arcadia Bay – and hits it hard.

In one timeline you’re too far removed (off in LA) to do anything, and so you listen to the destruction of Arcadia Bay over a telephone call before diving into the past in an attempt to divert the storm. In another timeline, you walk among the growing wreckage in the middle of Arcadia Bay as the vortex looms just beyond the shore – and you can choose to save (or not save) the precious few who cross paths with you.

Regardless of the specific timeline, there is a constant theme to the time vortex, trial by error. True to some of the recurrent Groundhog’s Day themes in Life is Strange, it initially seems that the only way Max can prevent the storm from happening, or at the very least prevent everyone from dying, is by failing repeatedly. When you mix in Jefferson, this becomes quite a daunting task for both the player and Max – and eventually you are forced to just accept that maybe there is only so much you can do after all, and maybe this storm just simply has to happen.

In a late-game bit of desperation, you can choose to reveal either nothing, something, or everything to a few characters (assuming they are still alive) – the most “important” of which is Warren Graham, who depending on a myriad of choices might be romantically involved with Max at this point, or simply just acquaintances, or anything in between.

Warren, a science-bro with a heavy dash of “I want to Believe” Mulder-style in him, is probably the most important person Max can talk to at a non-superficial level towards the end of the game if you want to get a bit deeper (but not much) into what the hell is going on. Turns out, no one can tell for sure (what a surprise), but Warren has a pretty good guess – which canonically turns out to be correct – Max has created a shit-storm of a time loop which is not only ripping apart time itself, it’s also killing Max.

You might be thinking “Whoa, hold on, how did dude-bro know all that?” Well, he didn’t, I’m sort of expanding on and extrapolating from the conversation based on what you know as the player. In fact Warren’s guess is pretty rudimentary, but if you’ve done enough watching and digging as Max, then Max sort of fits the pieces together herself, and when you add in your player knowledge, you get at least a semi-coherent picture of what is going on.

Essentially, when Max gained her power, she simultaneously had a premonition of what would happen if she used her powers. The thing is, there was absolutely no way of knowing what that meant at the time, and further, wouldn’t there be some way to avoid this entire metaphorical shit-storm from happening? I mean the entire game is Max trying to prevent the evil of Jefferson and the chaos of the storm. If trying to save Arcadia Bay has created a time loop that is slowly spiraling out of control and slowly killing Max each time she alters time, what can you possibly do?

The answer is surprisingly simple, yet profoundly frustrating. You have return to the original timeline, and stick to it.

In other words, you can’t play God.

…Or can you?

The Choice

And herein Life is Strange becomes one of the most divisive games I’ve seen.

You see, after everything you’ve done. Every. Single. Thing. Every conversation you’ve had, every door you opened, every life you saved – or ended, something becomes increasingly clear: You altered fate. You upset the hand of God, and now you must bear the consequences. Pretty heavy stuff for a teenage girl simulator. But what exactly did Max do that was so egregious that time itself decided to wipe Arcadia Bay from existence?

Again, the answer is simple.

Max prevented Chloe from dying in the bathroom of Blackwell Academy.

That brief moment with the blue butterfly wasn’t just a visual cue for the ensuing chaos effect, it was a homage to Chloe (blue + blue). No one, neither the player nor Max could have had any possible idea what that moment meant at the time. But remember how Max took a photo of the butterfly right as it landed – and also how Max can revisit moments in time via a photograph? Things starting to make sense?

The storm is the result of Max changing time. That she saw the storm just before unlocking her powers was no small coincidence. The foreshadowed storm was essentially a warning sign (sent by entities or forces unknown, could be God, could be the universe itself, could be the squirrels) which said that “If you alter time, then there will be chaos.” And, not knowing this, Max proceeds to massively alter time – and it all starts with the precise moment that she prevents Nathan Prescott from shooting Chloe Price. The result? The only way to stop time from unraveling is to go back before Max even used her powers, and then to refuse to use them. In effect, the only way to stop the time vortex from destroying Arcadia Bay and its inhabitants is to let Chloe die.

But true to it’s premise, Life is Strange doesn’t force your hand. You are given a choice. A final choice.

Do you sacrifice Chloe, or sacrifice Arcadia Bay? There is only one way forward.

And here, sitting on the cliffs above Arcadia Bay, Life is Strange makes you realize something. Since you originally broke the time stream, “fate” has tried to reclaim Chloe on multiple occasions. This ranges from the more temporally abstract – such as when saving Chloe’s Dad (William) results in Chloe dying rather than William.

Then there are also the more direct outcomes such as Jefferson shooting Chloe in the head, to even the more “random” such as Chloe’s foot getting stuck in a train track and the only thing that saves her is Max’s power (once again).

Almost like the beat of a barely audible drum, Chloe’s mortal end is a subtle pulse beneath the entire flow of Life is Strange. And, unlike those extremely corny “Final Destination” movies, it’s never overt. The game wasn’t designed in a manner that made it about saving Chloe from death across multiple realities, but in practicality, that is precisely what it had become – the “answer” was hiding in plain sight so to speak. And here Life is Strange reveals one of its greatest secrets, all along Max wasn’t really after Jefferson, she was trying to save Chloe (physically and emotionally). Max wasn’t really trying to stop the storm, it was secondary to trying to rectify the problems she had caused – most namely, by saving Chloe from a myriad of deaths and objectively bad outcomes.

Was Jefferson “bad?” Without a doubt. Was he the true antagonist of the game? Without a doubt. But Life is Strange turns out to be much deeper than a detective quest. While Max might fill the role of Sherlock Holmes, and Jefferson James Moriarty, that really isn’t the core of the story. Essentially the entire game is a subplot to the theme of consequences. For the vast majority of Life is Strange, Max is almost indignant against fate and time, altering it at her will and really only dealing with the physical consequences to herself. And while bringing about Jefferson’s downfall is a noble production, Max became an “actor” in that play because she cheated. She broke the rules of time. And as a result – she has to pay the consequences.

Which loops me around to an earlier point – can you play God?

In Life is Strange the answer is yes – but only if you accept, as Damocles learned too late, God’s burden.

So you have to choose: “Undo” everything you’ve done. Every single action, every life changed. All your blood, sweat, and tears – undone in an instant as you go back to where it all began and choose to do nothing. Or, you can chose to save Chloe, essentially spitting in the face of fate, but in doing so you, you, doom Arcadia Bay.

Would you take a life to save a myriad of others? Or would you save the others, at the expense of the one person among all of them who matters the most to you?

That is final decision of Life is Strange.

And, unsurprisingly, whichever way you decide the “Choice,” the ending of the game is vastly different. And I do mean vastly different. But you can’t “rewind” here, the very crux of this choice is to either make the conscious decision to move forward in time and let the storm rage on, or to go back in time and “restore” the timeline. Either way, Max’s powers are a moot point.

While seeing the different ending in it’s full effect essentially requires replaying the entire game, there is this cool thing called YouTube that I used to watch a “Full” (e.g. no shades of gray) version of the ending I didn’t pick. So I’ll discuss both of them here.

Ending 1 – “Sacrifice Arcadia Bay”

Life is Strange doesn’t punt here, when it warned that the time vortex would destroy Arcadia Bay, it wasn’t kidding.

In this ending Max chooses to sacrifice Arcadia Bay in order to save Chloe and as a result, Arcadia Bay gets obliterated along with seemingly everyone in it. While the game does drop a few minor hints that maybe not every single person dies (such as a blanket having been placed over a body the following morning), the implications are strong that most of the town is dead and the town itself is now a wasteland. But Chloe and Max aren’t so fortunate to just go gallivanting off into the coastal bluffs, instead they have to drive Chloe’s truck through the ruins of Arcadia Bay on their way to greener pastures.

And while there is definitely an air of “things will get better” for Max and Chloe, the haunting reality is that you just let an entire town of people – the good, the bad, and the in-between – die so that Chloe could live. And beyond that, there isn’t a whole lot more to be said for this ending. While there is certainly no resolution towards what the future holds for Max and Chloe, the ultimate message is that they survived the storm.

Though Arcadia Bay did not.

Ending 2 – “Sacrifice Chloe”

Ending 2 is the polar opposite of Ending 1. Here, Max decides to return to that fateful moment in the girl’s bathroom at Blackwell Academy and instead of saving Chloe with her powers, she lets her die.

And as Chloe dies, the blue butterfly gracefully flutters away.

Soon after the bewildered Nathan Prescott is apprehended by none other than David Madsen, and, with Nathan’s confession (and the constant fact that his family has power),there is enough to find Rachel Amber’s body and bring Mark Jefferson to justice for that and other crimes.

From there, things seem mostly to “balance out,” for instance, with the truth out in the open Kate Marsh no longer attempts to kill herself, thus negating the need for Max’s supernatural assistance. Further, Frank (the drug dealer who I haven’t discussed too much here, but was a close runner up for my five character section), also learns the truth about Rachel Amber (who he was in relationship with) and subsequently calms down quite a bit and even attends (from a distance) Chloe’s funeral.

Really, the funeral is sort of the backdrop of this ending, as the music plays over a montage of a few events while the funeral is playing out.

Though things aren’t really good, they are right, as time’s flow has been corrected.

The “True” Ending

So, which of these endings is the true ending?

Well, the beauty of Life is Strange is that the canonical ending is entirely up to the player. While developers might throw their hat in one bucket or another – I generally don’t value a developer’s belief towards an ending anymore than I do a random player’s. I think art takes on a life of its own, irrespective of the creator, and in this regard Life is Strange is a sterling case study. The “True” ending is whatever you craft over the course of hundreds of decisions based on Max’s actions (and more specifically, her actions through You).

Now, having said that, let me explain why Ending 1 is the wrong ending and why Ending 2 is in fact the correct ending (a stance which tends to make me the frequent target of rage in the game’s community). 🙂

For starters, if it wasn’t obvious, I chose Ending 2 and I chose it without a whole lot of soul searching, mostly because despite everything Max and Chloe had been through, sacrificing an entire town just didn’t feel right to me. So I didn’t. I also didn’t like the aspect of Max standing against time itself, it seemed like a battle that would never end.

For instance, in Ending 1, Max “saves” Chloe at the expense of Arcadia Bay. Ok. But not really. There are a load of problems in this ending. For starters, we have no definitive confirmation that Jefferson dies in the storm – and since the timeline was so jacked up at that point – we have no idea if he was ever captured or killed by Madsen either. This means that the central antagonist of the game could very well get off scot-free in Ending 1. Second, while Max cares deeply about Chloe, it seems entirely, ENTIRELY out of character for her to let the entire town get destroyed. You spend the entire game bopping around trying to help people, and then suddenly just let them go – it doesn’t pan out from a character development standpoint. Third, and here is the big one, there is no reassurance that time won’t just keep on trying to kill Chloe’s ass. Sure, Arcadia Bay may have “atoned” for Max’s “sin” – but who is to say that the time vortex won’t simply follow Max? Ending 1 answers none of these questions and in my opinion, not dealing with the fact that Chloe should still be dead makes Ending 1 a weak ending. Whereas the time vortex was the answer to Max’s “God Delusion” – Ending 1 seems to say “Oh, so now that the town is gone everything is good.” No, that makes no sense, and thus Ending 1 is wrong.

Ending 2 is correct because it not only canonically makes sense, it also leaves us with the fewest number of unanswered questions (though make no mistake it still leaves us with a few). It’s also much longer and more detailed, which arguably hints at which way the developer was leaning – though again, life of its own and all that.

Further, ending 2 is just more complete, for example Ending 2 also neatly wraps up the loose ends that Max had partially wrapped up, or attempted to wrap up, while destroying the timeline, whereas Ending 1 leaves them largely unaccounted for. I’m not saying it wraps them up in a happy way, but it does wrap them up. The most obvious factor is that Chloe dies for good in Ending 2 – and since Chloe was meant to die, then Ending 2 sees the timeline restored. Second, Nathan Prescott, in killing Chloe, leads to Jefferson’s downfall and the discovery of the truth behind Rachel Amber’s disappearance. Max was never meant to stop Jefferson herself, the cosmic irony of her entire journey was that if she’d just let Chloe die, Jefferson would have been stopped anyways. Third, much of what Max gets involved with because of her disruption never comes to pass – e.g. Kate’s suicide and the time vortex.

The result is that time “takes care” of things, Max doesn’t need to use her powers, because doing so imbalances everything. In fact, the entire time the vortex was just the universe trying to re-balance things. Which, upon closer inspection, makes you wonder whether or not it was actually Max who was the chaos, not the storm.

But as mentioned, make no mistake, when Max “rights” the staggering timeline, she isn’t leading us to a happily ever after finish in Ending 2 (if anything, Ending 1 shows just how problematic such a goal is). No, things are still “wrong,” but they are now wrong in the right way: Chloe’s dead, Nathan’s mental illness may (or may not) now be addressed but either way he has now committed two homicides, Jefferson is caught but he still “ruined” Nathan and killed and kidnapped unknown numbers of people, Madsen is forced to bury the stepdaughter he couldn’t save, Joyce has now lost both William and Chloe, characters such as Victoria never “learn their lessons” as they do in Max’s timelines, Rachel Amber is still dead, and any relationships you built with the various characters are effectually reset (for better or worse).

In essence, life, with all it’s beautiful problems, has returned to being “normal.”

Because of this, Ending 2 represents the tabula rasa that is most internally consistent with the entire message of Life is Strange, which again, is about consequences.

And, as if it needed any further confirmation of being canonical beyond the blue butterfly at Chloe’s funeral, at the very end of game (with Spanish Sahara by Foals playing in the background) Max offers up a faint smile as she gazes out at the sunset.

Because life may be strange, but it’s still life.

Interpretations, Variations, and Responses

While I obviously favor Ending 2, there are many, many, (wrong 😛 ) people who prefer Ending 1 – and while I disagree with them, I’m glad that Life is Strange can result in so many different interpretations, variations, and responses. This not only plays out in the game itself, but in a more meta sense in how players feel about the game and its conclusion.

One of the biggest in-game things that I had no idea about was the fact that Max and Chloe can end up in love, not like friend love, but relationship-love.

Yep. Of course that last kiss is all you get, so if virtual 18 year old lezbeans are your thing then Life is Strange doesn’t have much to offer. But what’s great about the Chloe-Max relationship is that for some people, such as myself, it never even begins to happen. You’d think that something as big as the protagonist and deuteragonist being in love with each other would be a core part of the plot, but in Life is Strange it doesn’t have to be. Whether or not Max kisses Chloe at the end, or simply hugs her, is entirely dependent on the extremely long line of choices you’ve made. So, for people like me who apparently aren’t in tune with their inner lezbean, I had no idea that this was even possible. In fact there were times where I thought to myself “You know, they could totally lez out, but I’m glad the developers didn’t do that, because it doesn’t mesh with how I see Max.” and what do you know, the developers made it so you can have it either way, or shades of gray in-between. If you don’t make certain decisions towards that end, it won’t happen, and you’ll subsequently have no idea it’s even in the game until you look to external media or replay the game (and make the necessary choices). In fact, when I first saw the image of Max and Chloe kissing, I thought it was fan art, but no, it can actually happen.

And if you are a closet homosex and fearful of such things, have no fear, you can also kiss Warren.

Or you can kiss neither of them, or you can kiss BOTH of them. It really depends on how you choose to live out the story, and it’s what makes Life is Strange great. In my play-through, I think Max ended up as an asexual demi-Chronos or something, because my Max had pretty much no romantic attractions to anyone. It might be because I just consciously made a series of non-romantic decisions, but it might also be because I was far more interested in digging up skeletons than I was in 18 year old romance, and therefore I was subconsciously guided down a path much more akin to a detective novel than a chick-flick with Sci-Fi elements.

But again, in Life is Strange the possibilities are numerous, and they ultimately rely on you.

And on that detail at least, people have been pretty freaking ecstatic about Life is Strange.

However, to say that everyone likes Life is Strange is a bit of stretch, and even a substantial minority of those who enjoyed the game absolutely abhor the ending (either one). The biggest complaint seems to be with Ending 2, because Ending 1 people tend to be more self-centered.

While that might sound like an insult, I don’t mean it that way. But if you choose Ending 1 and feel good about it (and more power to you if you do) then you’ve decided that Max’s (and your) personal connections to Chloe are worth destroying an entire town for – and further, you’re willing to deal with the consequences of upsetting time itself – regardless of any long-term consequences that maybe even Max doesn’t foresee (e.g. my concerns above about “fate” stalking Chloe endlessly and more time vortexes, etc.). An Ending 1 person is content with wanting what they want, come what may – so they are inherently self-centered because an entire town and future stability is sacrificed in favor of the immediacy of saving Chloe for personal reasons. As such, they tend to be more secure in their overall ending, though some of them might not like that so many questions remain.

For Ending 2, you have two camps – those who couldn’t bring themselves to pick Ending 1 because it’s wrong, but who really didn’t like that final choice and the fact that the game leaves so many unanswered questions. Then, on the other side of the fence, you have those who really liked Ending 2, but still don’t like the fact that so much goes unanswered.

And then there are those (me) who both like Ending 2 and are content with the “not knowing.”

I’ll address each of the unsatisfied opinions:

The “Discontented” Crowd who Hated the Final Choice

To these people, I – as nicely as possible – say deal with it.