Greetings!

This is likely my last or second-to-last post for 2017, so I’ve decided to have a bit of fun! One of the best things about traveling is getting to learn more about other cultures – or, as Mark Twain once put it:

“Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one’s lifetime.”

The holidays are an especially good occasion for such exploration, and SB and I have definitely taken to trying to learn more about Iceland’s Christmas traditions. In this post I’ll share what I’ve learned, though the obvious caveat here is that I don’t know Icelandic, so I’m mostly relying on translations and interpretations of other people. That said, I’ve relied almost exclusively on materials written in English by Icelanders, so hopefully I don’t share any egregiously incorrect information! So let’s get started!

The first thing to know about Iceland’s Christmas (Jól) traditions is that they can trace their lineage well into the mythos of Icelandic folklore. These are, by and large, not modern tales woven to sell you Christmas cards. They’ve certainly been streamlined, modified, combined, and clarified over the years – but the basic foundation is extremely old. These customs are also much more… “old world,” than those cuddly feel-good Christmas tales which have largely been adopted into mainstream U.S. culture. If you thought coal was cruel, how does being torn to shreds by a giant cat sound? Yep.

I, however, find these tales to be far more interesting – indeed, the older more “raw” versions of classical tales which lack their contemporary filters often appeal to me far more than their Hallmark Channel counterparts. The core messages are still roughly the same: be kind, love your family, and be festive. The difference here is that yo’ ass gets eaten alive if you’re naughty. Hard lands breed hard men.

So, with that framework in mind, let’s discuss how things work. Here I should probably note that a lot of the modern iterations of these characters stems from Jóhannes úr Kötlum’s 1932 poetry book, Jólin Koma (“Christmas Is Coming”). So while there are a lot of different very-very-old tales from which these characters are woven, that modern source is the primary basis for this post.

First off, clear your mind of Santa – he wouldn’t last a night in the harsh world of Iceland’s folktales. Instead, think of the 13 “Yule Lads” also known as the Yuletide-Lads or Yulemen – or in Icelandic, jólasveinarnir or jólasveinar. These 13 “lads” are trolls (or half trolls, not entirely sure as different sources referred to them as both) who come to visit the human population of Iceland around the holidays. The Yule Lads make up, what I would call, the crux of the Christmas festivities here in Iceland. But in order to fully understand the importance of the Yule Lads, we must first discuss their mother, Grýla.

Grýla is a troll/giantess who is said to currently live in a cave somewhere in the Dimmuborgir lava fields (which, as you will soon see, is somewhat fittingly where Satan came crashing down from Heaven in Icelandic Christian folklore).

Here Grýla lives with her somewhat lackadaisical third husband and father of the Yule Lads, the troll Leppalúði – but we’ll talk more about him in a second. Grýla is noteworthy for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is that she is very, very old. She was first referenced in text during the 1200s, so it’s not unlikely that she’s even older than that. Grýla’s death has been noted more than once, but the old troll seems to know to cheat death itself, because she just keeps coming back to plague the Icelanders, specifically Icelandic children – and by plague I mean drag them screaming into the blackness and eating them alive.

The good news is that Grýla apparently only goes on her carnivorous quest around Christmas, meaning that your chances of meeting a terrible fate at her hands are restricted to at least a small slice of the year. Further good news, Grýla can be staved off simply by resisting the urge to be naughty. Due to some mythological rule-set, or perhaps just a very odd sense of morality, Grýla only eats bad children. If you found the prospect of coal to be a lukewarm deterrent to engaging in the oh-so-much-fun act of being naughty, perhaps a savage death is a bit more of a barrier to naughtiness.

Now, if you might be thinking that Grýla’s husband Leppalúði is likely to be just as malicious of a character. Turns out, not so much. I mean, he looks mean and probably isn’t the type of creature you’d want to run into in a dark cave, but in comparison to Grýla he’s quite tame – and apparently quiet lazy (or at the very least, aloof).

Now, with a wife like Grýla it’s not surprising that he definitely appears to be the submissive partner in the relationship. Add in the fact that Grýla just up and ate her first husband (and let’s be real, likely her second husband too) and you get an environment in which ole’ Leppalúði has probably learned to keep his trap shut and just tend to the cave and the children like a good husband. Indeed, Leppalúði – at least from what I’ve read – seems to be a bit of a (comparatively) mild-mannered homebody who mostly keeps the feck out of Grýla’s way (can you blame him?) and who probably spends most of his time dealing with the Yule Lad’s antics. In some ways the Yule Lads might be described as the balance between Grýla’s evil antics and Leppalúði’s buffoonery. The good news for us humans is that Leppalúði doesn’t seem to go hunting for people in the same fashion as his wife does.

That’s not to say that Grýla is the only bad news. While her husband might be tame, and while the Yule Lads are, as we will soon discuss, prone to mischief as opposed to murder, Grýla also owns a giant cat known as the Yule Cat (Jólakötturinn or Jólaköttur).

Now let’s be clear, this is not your average domestic cat. The Yule Cat might better be described as a “monster” in that it is huge and hungry for humans. Whereas its master (Grýla) preys on naughty children, the Yule Cat hunts down and ravages those who haven’t gotten any new clothes to wear prior to Christmas Eve. Oh, and lest you big-people think you are safe, the Yule Cat eats adults too – though naturally children are of course also on the menu!

So now you’ve got a nice picture of Mom ‘n Pop and their carnivorous cat, so let’s discuss the real stars of the show, the Yule Lads.

There are, in the modern iterations, 13 canonical Yule Lads (though this number has drastically varied over the lads’ long and storied history – see my comment about Jóhannes úr Kötlum above). Unlike their baby-eating mother, lazy father, and deadly pet, the Yule Lads care much more about being mischievous and having fun (mostly for them, less so the people they annoy) around Christmas time. A lot of this stems from the fact that their mother keeps them locked away for most of the year, unable to explore the great outdoors. It’s only around Christmas that she lets them out to play – or perhaps Leppalúði just doesn’t have the energy to corral the Yule Lads while Grýla and the Yule Cat are off eating people. Regardless of the exact manner in which they are able to get out and about, the 13 Yule Lads start to “come to town” one at a time on December 12th, and each Lad has a different set of characteristics which define the antics they get themselves into.

The 13 lads, with English translations, as well as their arrival and departure dates are listed below.

| Icelandic name | English translation | Description | Arrival | Departure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stekkjarstaur | Sheep-Cote Clod | Harasses sheep, but is impaired by his stiff peg-legs. | 12 December | 25 December |

| Giljagaur | Gully Gawk | Hides in gullies, waiting for an opportunity to sneak into the cowshed and steal milk. | 13 December | 26 December |

| Stúfur | Stubby | Abnormally short. Steals pans to eat the crust left on them. | 14 December | 27 December |

| Þvörusleikir | Spoon-Licker | Steals Þvörur (a type of a wooden spoon with a long handle – I. þvara) to lick. Is extremely thin due to malnutrition. | 15 December | 28 December |

| Pottaskefill | Pot-Scraper | Steals leftovers from pots. | 16 December | 29 December |

| Askasleikir | Bowl-Licker | Hides under beds waiting for someone to put down their “askur” (a type of bowl with a lid used instead of dishes), which he then steals. | 17 December | 30 December |

| Hurðaskellir | Door-Slammer | Likes to slam doors, especially during the night. | 18 December | 31 December |

| Skyrgámur | Skyr-Gobbler | A Yule Lad with an affinity for Skyr. | 19 December | 1 January |

| Bjúgnakrækir | Sausage-Swiper | Would hide in the rafters and snatch sausages that were being smoked. | 20 December | 2 January |

| Gluggagægir | Window-Peeper | A snoop who would look through windows in search of things to steal. | 21 December | 3 January |

| Gáttaþefur | Doorway-Sniffer | Has an abnormally large nose and an acute sense of smell which he uses to locate laufabrauð. | 22 December | 4 January |

| Ketkrókur | Meat-Hook | Uses a hook to steal meat. | 23 December | 5 January |

| Kertasníkir | Candle-Stealer | Follows children in order to steal their candles (which in those days were made of tallow and thus edible). | 24 December | 6 January |

As you can see from the table, each Lad arrives on a separate date, and they stay “in town” until all of them have arrived, upon which they start departing – again one at a time – back to their mountain home. In total, this means that the Yule Lads are causing chaos in some format or another from December 12th all the way until January 6th.

If this story has seemed a bit… unpleasant.. thus far, what with the deadly endeavors of Grýla and the Yule Cat, coupled with the Yule Lads’ seeds of chaos, and Leppalúði’s “meh whatever” attitude about all of it, then have no fear, things perk up from here. While the Yule Lads have changed a bit over the centuries, their current manifestations are also known for bringing presents to those who act properly! Of course at a basic level you need to be good (lest their mom find you), and you also need new clothes (lest their cat eat you), but also need to leave one of your shoes on the window sill of your room to let the most-recently arrived Yule Lad know you are there! If you really want their good graces, you will also leave them a treat – but make no mistake, this isn’t a one-size-fits all cookies-and-milk fallback. Each Yule Lad has their own preferred “treat” and you don’t want to mix them up! Some are easy to remember, for instance Skyrgámur (Skyr-Gobbler) likes Skyr most of all. Whereas others, like Þvörusleikir (Spoon-licker) have less obvious tastes, such as carrots . Still, others, like Stúfur (Stubby) are likely to eat whatever you leave them without much fuss. In addition to food, you can also leave certain Lads items such as spoons (wooden!) or candles.

If you follow the proper protocol, you’ll likely to wake up to a present/treat of your own in the shoe you left out (as well as some classical Yule Lad mischief). However, if you don’t follow the proper traditions and/or are naughty, you’ll just get an old potato! An old potato might not be much, but it’s better than being eaten alive, though the potato is probably a warning sign that you need to start cleaning up your act real quick-like, lest Mommy Dearest find you.

It’s also important to note that the Yule Lads, much like their foreign counterparts, only come at night. Being trolls (or half trolls) and living in a dark cave most of the year has made their eyes sensitive to the light, so be sure not to leave too many lights on when you leave out your shoes and treat – the Yule Lads see far better in the dark! If you do find yourself face to face with a Yule Lad, a surefire way to get their good graces is to wish them a Gleðileg Jól (Happy Christmas).

It’s also worth noting that if you follow the proper procedures and have a bit of faith, that the Yule Lads have been known to travel far beyond Iceland’s coasts to leave presents for those who tempt them with especially good treats. So if you aren’t in Iceland, but still want to participate in some Yule Lad fun, you know what to do – just watch out for Grýla and her monstrous cat.

So there you go, a nice primer on the Yule Lads and their crazy family.

But that’s not all that goes in Iceland during the holidays. While the Yule Lads provide the backdrop to the season, there are a few other events and traditions that are widespread.

The first is Aðventa (The Advent) which starts on the fourth Sunday before Christmas and is the “official” start of the season in Iceland. It’s also when most of the Christmas lights begin to appear. In addition to modern lights, traditional Aðventa came in two formats: an Advent Wreath with four candles (one for each Sunday of Advent), and a seven-candle candelabra which was, being quite bright, was believed to keep out the winter’s darkness.

If this talk of lighting has you wondering about Christmas trees, then have no fear, Iceland has those too – though they are a more recent phenomenon in the manner you probably imagine a Christmas tree. For most of Iceland’s settled history there really weren’t that many trees that could be cut down, so the Christmas trees were made of wood scrapped together from other things, and then mounted with juniper branches and candles. As Iceland “opened” to the world (and attempts at reforestation began), real live Christmas trees became more accessible, and today most Icelanders use Christmas trees which appear much like those you’d find elsewhere – and they predominantly use real trees as opposed to fake ones. One interesting note is that the Christmas trees themselves often weren’t (and aren’t) lit in the home until just a day or two before Christmas, but the lights are left up until January 6th (which just so happens to be the last day the Yule Lads are around).

Second, I’m sure you’re wondering about food. Well, there’s all sorts of it, just like anyplace else. A few notable examples are the vast array of cookies which get baked, as well as the staple of Laufabrauð – which, directly translated, means “leaf bread.” The baking of the Laufabrauð is a family event, and great care is put into making the Laufabrauð as fancy as possible – sometimes it ends up so fancy that it gets turned into decorations as opposed to being eaten! Laufabrauð is generally served during both Christmas and New Year’s, paired with delicious smjör (butter).

There is also a traditional drink which is a mixture of locally produced malt (Maltöl) and orange soda (Appelsín). The mixture, Malt og Appelsín, is so popular that it can be purchased pre-mixed as Jólabland (Christmas Mix), though many Icelanders still take the time to mix it themselves. The exact ratio of malt to soda is hotly debated, and that’s territory I shan’t risk entering. 🙂

While foodstuffs beyond the sweet include the scrumptious fare that you might imagine for Iceland, including: herring, smoked and cured salmon, reindeer pâté, smoked lamb, roast pork with rind, rack of ham, turkey, and more – December 23rd brings about something a bit more intriguing, Skötuveislur or fermented skate. Skate is a type fish, which as you might have guessed, has been fermented. Traditionally this one done by sealing the skate in a closed container for a month or more (sound familiar?). The resulting dish is known just as much for its extremely pungent smell as its taste. In fact, I’ve been told that the smell is so difficult to get out of your house that a lot of people opt just to go get Skötuveislur from a restaurant these days. I’ve yet to try this delicacy, and honestly after kæstur hákarl I can’t say I’ll be seeking it out. That said, it’s still a strong tradition, so if you find yourself in Iceland on December 23rd you’ll know what that pervasive smell in the air is!

Perhaps the smell of fermented skate brings about thoughts of the afterlife. As on December 24th (and on New Year’s Eve) Icelanders remember their departed loved ones. They do so by visiting cemeteries and leaving candles on the graves of the departed. One of the most aesthetic cemeteries during this time is Hólavallagarður, a cemetery from 1832 which overlooks Tjörnin – so not very far from us at all.

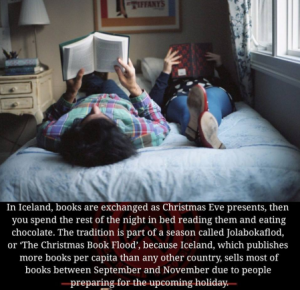

There’s also the “Christmas Book Flood” which you may have seen as the following image floating around social media.

In Icelandic this is refereed to as Jólabókaflóð (The book flood of Christmas), and it’s largely true to the tidbit being passed around the interwebs. The one big difference is that it’s not quite as confined as the image makes it seem (its more chronologically far-reaching), but it’s still a big deal (and yes chocolate is a part of it). A few weeks ago SB and I noticed that the stores were starting to accumulate a TON of books – we had no idea what was going on at first, but now we do! And for reference, I mean, literal tons of books.

Once you’ve got your new collection of books, you have to be careful, as the holiday season brings bonfires to Iceland – and I mean a lot of bonfires. Long before fireworks made it to the arctic north, bonfires served essentially the same purpose – the symbolic burning of the old year, old sins, and the celebration of bright futures to come. The many “brennur” (burns) are community events and occur mostly on New Year’s Eve and The Thirteenth Night. Also, these aren’t just piddly little campfires, these are legitimate bonfires.

While fireworks have since joined the ranks of Icelandic New Year’s traditions, the bonfires remain.

Finally, as the season winds down, we come to Þrettándinn, the “Thirteenth Night” (the equivalent of the Anglo-Saxon “Twelfth Night” you might be familiar with).

Like New Year’s Eve, bonfires are prevalent during Þrettándinn – but Þrettándinn is also a night of great, ancient, mystery. In Icelandic folklore, Þrettándinn caused strange and mythical beings to stir from their slumber. Many of these awakenings could be dangerous for humans (such as talking cows which would drive those who listened to them mad), and others, such as seals which shed their skins and walked among men, were just downright creepy. Þrettándinn, the official end of the season, also sees elves come out en masse (including the elf “king” and “queen”), as well as other mythical creatures and beasts. It’s also the final day the Yule Lads are in town, and if you make it through the night without falling victim to one of the various dangers of the dark, you’ll also know that Grýla and the Yule Cat have retreated back into the hinterlands for the year.

Like most other aspects of the season in Iceland, while evil and mischief lurk in the shadows, there is a great deal of symbolism to light, family, and the community. So stay close to the fire’s warm glow and those who you care about, and you’re likely to find yourself safe, full of delicious food, and spiritually satisfied even against the long dark night of Þrettándinn.

And that, dear friends, is Dinosaur Bear’s coverage of Jól. This is of course, not an even remotely exhaustive list, and as with any compilation of traditions, beliefs and practices will vary from one family to the next. It also leaves out a few important events, but this is a nice overview to the season, from an outsiders perspective with a focus on what seems especially “unique” to yours truly. I hope that if you’re new to all of this like me, you’ve found it especially interesting, and, conversely, if this is what you grew up with, that I didn’t get anything too out of whack. 🙂

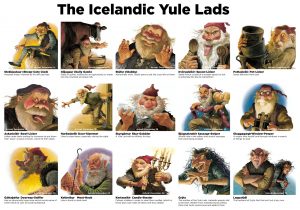

In closing, here is a nice “cheat sheet” of the cast-of-characters (sans Yule Cat) referenced within this post. I’ve left the image uncompressed for easier viewing.

If you’d like an English translation of the poem upon which the modern iteration of the Yule Lads are based, click here.

Until next time,

Gleðileg jól og farsælt nýtt ár!

-Taco

I am glad that the hungry cat will have gone back into hiding before I arrive. I don’t want any part of him.

But those cookies…yum!!!

Tristen isn’t a fan of the cat either, which isn’t surprising.

The cookies do look good!

At some point in time political correctness turned Gryla into a lump of coal here in the U.S.

I can only imagine what it would have been like at Christmas time as a child in Iceland sounds more like our Halloween either way I”m not sure as a child I would have been looking forward to all the carnage that might occur to my family

Wow what a tradition, Its amazing how different an solid these traditions can be rooted in cultures

Mark Twain nailed it even then for those that were diversified.

I agree, it’s easy to think that what you grew up with is simply what is, but in reality our reality is quite small. 🙂

Yay jól in Iceland! I’m loving getting to know their traditions, especially all the Yule Lads. With the food, my favorites so far of the laufabrauð and smoked lamb. Cookies can be added to that list, but that’s a normal thing for us in the US, as well. I really could see us taking some of these new traditions and keeping them going once we’ve moved back.

I really want to go see the cemetery before they take the candles and such down. I think it would be so pretty and eerie at the same time.

I agree! I hope we get a chance to go over there. 🙂